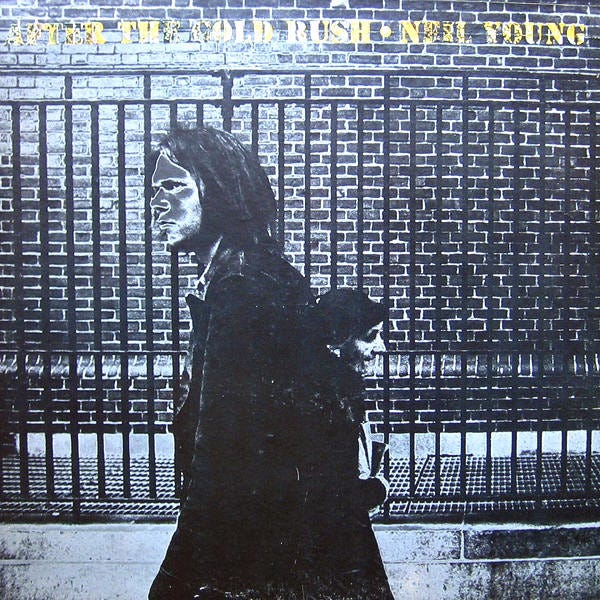

81. Neil Young - After The Gold Rush (Reprise Records, 1970)

California 1970. Neil Young is in a jam. Not the good kind. On the face of it, he's doing great; fame, lot of airplay for his three bands the Buffalo Springfield, his backers Crazy Horse, and Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young and lots of sales, but the bean counters at his label Reprise Records aren't so sure. Buffalo Springfield are on ATCO Records (and are recently dissolved), Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young are on Atlantic Records, so from the Reprise point of view, Neil isn't making enough music, in spite of the four albums he's been a part of in the last two years (artists were generally expected to put two albums a year in the can back then). They ask him for another, but he's touring all the time and a bit spent creativity-wise.

Peru 1970. In the last few years, the hippie lifestyle has taken hold of Hollywood, causing lots of far-too-inspired people to try to put the entirety of the psychedelic experience on film in spite of generally having no money. The guy who has come the closest is Dennis Hopper, whose film Easy Rider has proven an unlikely smash. His next project, The Last Movie, is a metatextual dream-logic western and it's destined to be as big of a fiasco as most of the rest of the pack (Maidstone, Psych-Out, Wild In The Streets, Free Grass!, The Hooked Generation, You've Got to Walk It Like You Talk It or You'll Lose That Beat, Zardoz), made redundant by his pal Alejandro Jodorowsky's El Topo. Hopper is in full creative control, increasingly unhinged, the script is on the floor and everyone is being given license to improvise. The one firm order Hopper does give is to actor Dean Stockwell. He tells him to write a script, for himself. Stockwell obliges, writing a film called After The Gold Rush.

On Stockwell's return to California, he takes up residence at a compound of creatives in Topanga Canyon, finishing his screenplay with the assistance of Herb Bermann (Captain Beefheart and his Magic Band). Also resident in the canyon is Neil Young. They quickly bond and he pitches the script, a metatextual dream-logic western, with environmental themes. Neil has been told to make “something” for months, but no-one has narrowed it down to “this thing”, and he has a soft spot for environmental themes. Neil gets inspired quick and gets to work. In the meantime Stockwell tries to pitch the screenplay with the talents of Neil Young and Dennis Hopper on board. What he hasn't grasped is that The Last Movie has arrived six months late and a tangled mess of logic (made more experimental at Jodorowsky's suggestion) meaning that Hopper is about to be told (for the second time in his career) that he will never work in this town again. After The Gold Rush is therefore a soundtrack without a film.

Neil Young has developed a particular way of working. He will agonise for hours, sometimes days over the technical side of things, inhabiting the role of instrument technician, producer and engineer until all the musicians can play music and drink beer without having to worry about much. He learned this from experience, there's a clip online which illustrates it pretty well: Stills, Nash and Young recording “Words (Between The Lines Of Age)”. The band is going just great until a technical hiccup out of their control derails the whole damn session.

Once the tech is laid down, the songs come very quickly. If he gets the gist of the idea of a song across, that's it done. Better to move on before anything boring happens. This dramatically affects both the lyrics and the song structure. If a guide vocal (words that don't yet mean anything but allow a vocal to be tested before a lyric is penned) sounds alright, it stays. If a song runs unconventionally short or long because it's a sketch or a jam, the length stays. Listen to “Till The Morning Comes”, it's meaningless and pitifully short, but it has the right mood, so it stays.

After The Gold Rush opens with the three notes most likely to open a country album, then immediately veers off. Neil's voice is at once conversational and tremulous and the harmonies of Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young are making a return (only Stephen Stills is actually present). The title track was actually written much earlier than Stockwell's script, but it carries the heart of the film, a California-centric yearning for environmentalism, a “Let It Be” for Planet Earth. “Only Love Can Break Your Heart” later launched the band St. Etienne, and that's more than enough for any song. The original is still better, sharpshooting the heart without saying why.

“Southern Man” admonishes Southern America for being sluggish to come to terms with civil rights and reparations. Lynyrd Skynrd composed “Sweet Home Alabama” in retaliation for his perceived generalisations. That song is now a towering enormity for the Confederate flag wavers of 2025. Reading about this feud, I don’t get the impression that the Floridians originally intended it to be embraced by J.D Vance’s boot boys.

“When You Dance You Can Really Love” describes that feeling of romance being easier when you're dancing, cause the person in front of you is graceful and you're both distracted by the obligations of the music.

These are songs in shorthand. There's no monologuing, only the slightest of statements to get to the feeling. They are written by someone truly animated by music. They are somehow both dreamier and more lucid than their contemporaries, dodging the pitfalls of hypermasculinity, technical excess and gurning pomposity. In life, Neil compliments other musicians a lot and he takes the compliments by musicians he likes with more pleasure than perks or accolades. Till it gets weird, then he just moves on to something else.

Did It Make Much Of A Splash?

The After The Gold Rush film never made it to preproduction. Dennis Hopper was blackballed and probably speedballed. Jodorowsky, the man whispering crazy in Hopper's ear, set to work on a strange path up the Holy Mountain and ever higher to an insurmountable Dune. Years later, Neil Young made his debut as a film director, Human Highway (1982), starring Dean Stockwell and a still deranged Hopper, as well as Young himself, and the creature known as Booji Boy (Mark Mothersbaugh, whose friends deaths Young had chronicled in his song Ohio). It's a very strange film, but it works well as a midnight movie. Jodorowsky failed to make Dune, which went to David Lynch, who also journeyed to hell and back trying to make something of the material. Lynch's film was a fascinating dud, rapidly embraced in Japan, but ridiculed at home for quite some time.

It did however introduce him to Stockwell and Kyle Maclachlan, who a year later all teamed up with Dennis Hopper, now sober, and Isabella Rossellini for Blue Velvet (1985). So it all worked out.

After The Gold Rush was not instantaneously canonized, getting a bit of a drubbing for not being fleshed-out enough. It's sure canonized now, along with it's artist, the “Godfather of Grunge”. Neil sure did influence a lot of that early grunge stuff, starting with Dinosaur Jr and Sonic Youth, but his impact goes far beyond that. More than anyone, he is a link between the Woodstock generation (he hated Woodstock) and alternative rock, artists like The Pixies, REM, Radiohead, Daniel Johnston, Flaming Lips, Meat Puppets, Beck, Phish, Smashing Pumpkins, Mercury Rev, Fleet Foxes, Songs: Ohia and My Bloody Valentine.

Where To Go From Here?

In the course of this review I went to neilyoungarchives.com looking for a bio. No such luck, but it is a thorough high-quality archive of Neil's music, with a UI that has to be seen to be believed. For a mere $500 you can also pick up a second-hand PONO filled with the music of Neil Young. I do not have the time to explain what a PONO is, but it is quite the thing.

At the time that After The Gold Rush was made, there were certainly all manner of rumblings of psychedelia and studio-oriented odd electronic production techniques afoot. In contrast, the more popular end of rock was experiencing a kind of calm in the 'electric' age, with country, folk, blues and hard rock striking up a short-lived truce before going their separate ways in the forever-electronic decades ahead. These ten records give a small taste of this air:

The Band - Music From The Big Pink (1968)

The Byrds - Sweetheart of the Rodeo (1968)

Steppenwolf - At Your Birthday Party (1969)

Creedence Clearwater Revival - Willy and the Poor Boys (1969)

The Flying Burrito Bros. - The Gilded Palace of Sin (1969)

Mountain - Climbing! (1970)

Lynyrd Skynyrd – Need All My Friends / Michelle (1970)

Van Morrison - Moondance (1970)

Tim Hardin - Bird on a Wire (1971)

Jackson Browne - Jackson Browne (1972)