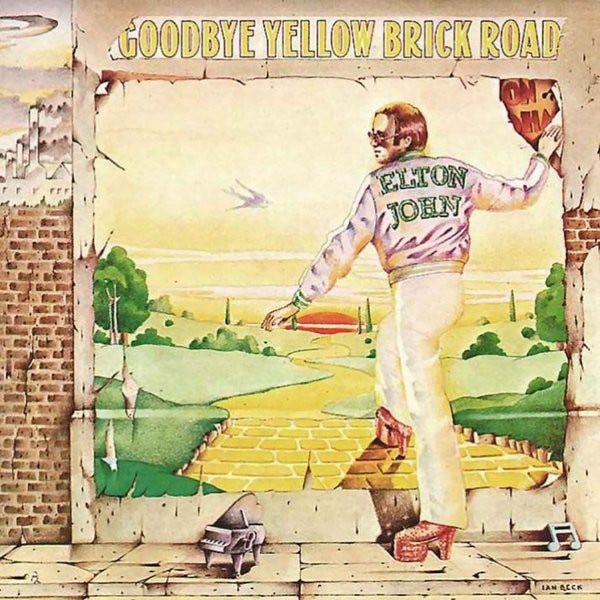

78. Elton John - Goodbye Yellow Brick Road (DJM Records, 1973)

Going into this review, I feel like I knew as much about Elton John as I did about the Crown Jewels, and that I would probably have some kind of snarky comparison to make about the two. I did know enough that such a jibe would have him snapping “Oh, fuck off!”. Coming out of it, I see this album as a window into a world of songwriting prowess and how it was supported in its age and a vital part of the conversation of pop.

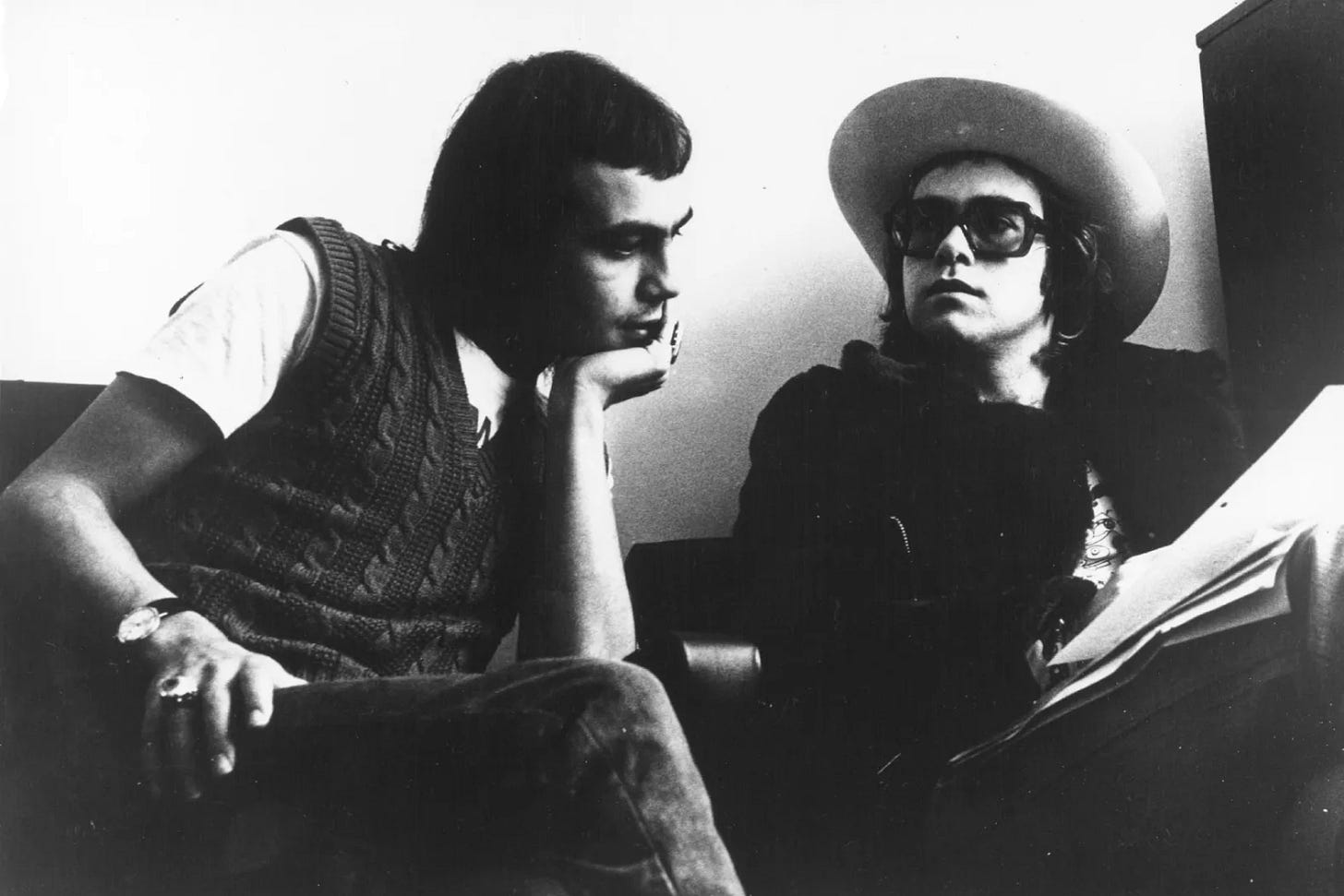

Elton John started his recording career young and well-trained, but in an age of songwriters of towering significance. He formed a healthy symbiosis with teenage songwriter Bernie Taupin, thanks to a stroke of good fortune. Taupin had written a letter into a music mag offering to write his poetry for a songwriter, but crumpled it up and discarded it only to have his mum send it in on his behalf. The duo got acquainted with Beatles publisher Dick James, who saw enough promise to divert a modicum of his ample resources to them.

Elton is a virtuoso vocalist. Solid blues centre, but can annunciate and sell a lot of verbose ideas. Can go rockabilly, country or folk as the syllable may require. He also has a knack for impersonating other singers (Dylan on “Hymn 2000”, Van Morrison on “Slave”). His piano playing is doing something similar too, slipping in and out of different genre ‘feel’. He hasn't been to America yet, but half his heart is already embedded there. As a lyricist, Taupin aspires to maturity. He has grown up seeing songwriting get more convoluted (his love of Marty Robbins developing into a love for Laura Nyro) and wants to start Elton from that place.

Together they have approached music more like a songwriting house than a band: quantity over quality, more focus on songs than singles or albums which is fine if some of your songs are gold nuggets. They are manoevring in what is about to be a post-Beatles world. They have the resources for bells, whistles and flangers. It is somewhat surprising that the first Elton John album starts with bongos but this decision stems from the same lack of confidence as the impersonations. In the early stages they get to meet some pretty talented folks (there's a peculiar series of musical exchanges with one Nick Drake at this point) and receive useful bollockings from Dick James and producer Steve Brown and Elton and Bernie come up with the song “Lady Samantha”, a commercial failure, but something they themselves enjoy.

Two and a half albums deep their luck is about to run out. They have a run of shows at LA's Troubadour with a healthy cash injection behind it and the whole band is instructed by management and label that if they fuck this up, they'll be leaving the music industry and entering the world of shoe sales (“I dunno, what are the hours?”). Elton can barely mentally cope with being hailed as the next best thing (introduced by Neil Diamond and with an audience comprising Crosby, Stills, Nash, Peggy Lipton, Van Dyke Parks, Linda Ronstadt, Don Henley, Brian Wilson and Quincy Jones, no pressure) and the gigs almost don't happen as a result. When he takes the stage, every trick he has comes out of the bag. There are the old school rock and roll moves (Jerry Lee Lewis shit), unseen for a day or two in favour of stool-bound solemnity, and the charm is turned right up, but it's the songs which see him through.

“Border Song” and “Take Me To The Pilot” possess a (the same) rising bassline, amped up to practically Jamaican levels on the mix of the latter, and are addicting slow boogie. “Country Comfort” has a lived-in Nashville via California feel, probably would have been a shock coming from the lips of a Brit. “Burn Down The Mission” possesses also-authentic hyperspeed gospel sections to keep the energy high, and is stretched to an seventeen-minute closer replete with a bit of Elvis and The Beatles thrown in for good measure. Most importantly perhaps is “Your Song”, the first song that is Elton John through and through, there's no trace of a borrow so it's an impressive act of unlearning. John Lennon (which is where the “John” in Elton John comes from) regards it the first move that songwriting made after The Beatles dissolved. Arses saved for now, the recordings continue, but there's a wrinkle.

See Elton and Bernie have made it, but the experience has not been an easy one for them. There's no grounding, no time to reflect on what works and what doesn't and both are “Yes, and...”-ing life, agreeing to do a soundtrack for a Paramount film and to break the rest of America at the same time. It's too much too soon. Madman Across The Water is a travesty of grandiosity that booze, weed and cocaine alone cannot explain, the songwriter must have been in love too. It begins with “Tiny Dancer” and then drives off a cliff into hellish pretension to the point where the presence of Rick Wakeman, the Tory wizard of synth tomfoolery, almost seems like a grounding influence.

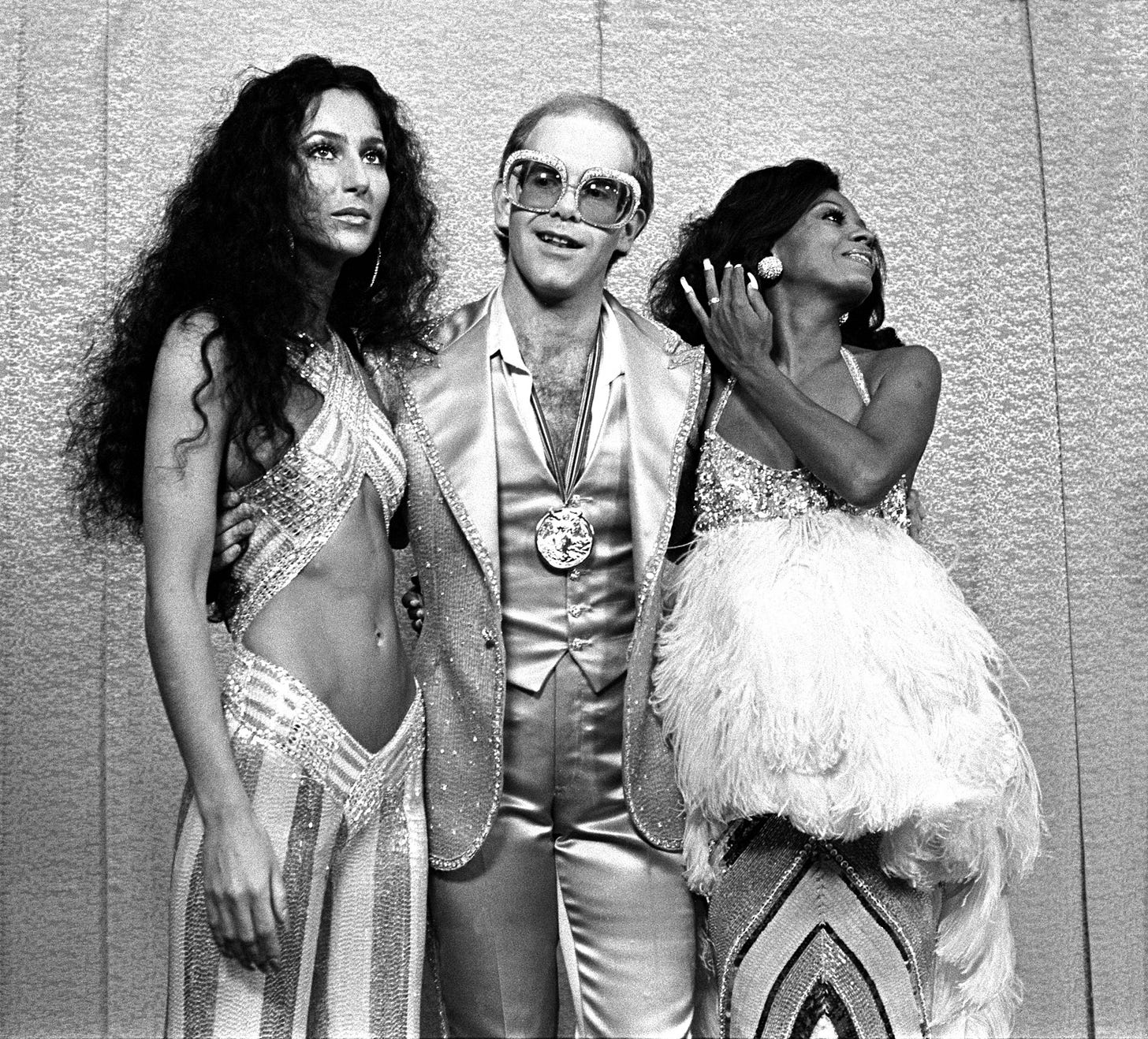

Fortunately, the times are about to bend in Elton's favour with the arrival of glam. Elton and Bernie begin taking advantage of the genre's uncolonized space and it's like the Bee Gees finding disco: the shoes fit, and they are both huge and sparkly. This marks the start of the winning streak where he gets to make his legend across most of the rest of the seventies.

Goodbye Yellowbrick Road has been chosen for this list most likely because it has a decent spread of singles (“Saturday Night's Alright For Fighting”, “Goodbye Yellow Brick Road”, “Bennie and the Jets”, “Harmony” and “Candle in the Wind”), but also because as a double-album it is the most generous offering from this fertile period. At auction it is often the largest master paintings which take the highest price.

The opening of this record is a barrage of well-deployed cheap tricks. “Funeral for a Friend” is a medley of the album ahead and was written as a kind of funeral procession for Elton John. He was hoping to die in the far-flung future by the sound of it (mission accomplished) as he invokes Wendy Carlos' state-of-the-art A Clockwork Orange score and foreshadows Jim Steinman’s Meatloaf dramaturgy. The grandiosity of this gesture would be a problem, were it not for the streamlining influences of glam and the glam-pedigree of producer Gus Dudgeon (whom Elton had been fond of since “Space Oddity”).

“Candle In The Wind” is a pretty early piece of gay iconography in song. This phenomenon goes back decades more, but it was at this point exceedingly rare that the fan (Elton) and the admired (Norma/Marilyn) are both named. The raw monodirectional merging of it paired with the contempt for everyone else give tastes of fandoms to come. Still faster than “Candle in the Wind”, “Bennie and the Jets” feels slow to the point of stasis, another dirge. Though satirical in intent, it feels like a still photo of audience teeny-boppers, awestruck before the band has even taken the stage. Then we get “Goodbye Yellow Brick Road”, about the death of Elton John as he wakes up in Kansas as Reginald Dwight, assuming his label don't assassinate him for quitting. I feel that the cover of this album is very much him saying hello to the Yellow Brick Road which is confusing.

“The Ballad of Danny Bailey (1909-1934)” and “Dirty Little Girl” together form a very ambivalent political stance. The former is a paean to lawless twinks, the likes of which Morrissey would get fond of writing. The latter reads like the tantrum of an upstanding NIMBY externalising their disgust. Both are at least provocative.

“Jamaica Jerk-Off” could be worse. Not by much. White rockers think Jamaica is a fucking hoot at this point and this song has badly-affected Jamaican accents from four of 'em. On the other hand it has a silly ska groove with pretty novel use of a drum machine. This whole album was meant to be recorded in Jamaica, but they ended up over there with good vibes and no gear, so it all got done in an eighteen-day cramming session in Paris instead. “Sweet Painted Lady” is the French number, replete with rat, accordion and one busy brothel.

“Saturday Night's Alright For Fighting” is a good tension-builder. Rocking in a Chuck Berry/Little Richard indebted pub-rock fashion, the verse sounds like a verse, the chorus sounds like a verse, it consciously doesn't satisfy until you get to the hyper-repetition at the end at which point a whole audience has something they can yell along to. Ask anyone to sing that song for you and watch as they skip to the end.

Did It Make Much Of A Splash?

Elton was already a phenomenal high-roller when this was put together. A month before it was released, he played The Hollywood Bowl, five unplayed grand pianos in the background, painted to spell out the word E-L-T-O-N. Tacky is an important part of glam, but boy was he pushing it. Still, it got him on the Muppets.

Rock critic Taylor Parkes once said of fellow Muppets guest John Denver that Kermit and co. “took him in as their own” because he “shares their physiognomy”. I see the same physiognomy in Paul Williams, composer of The Muppet Christmas Carol, and also, of course Elton John, who at one point looked like he'd got in a teleporter with the Mahna Mahna guy. He sucked on that show though, possibly a humour mismatch, sobriety, lack of control or maybe just a fear of being seen as Bernie Taupin's puppet.

As for influence, take your pick. The bass so good it was used twice on “Border Song” and “Take Me To The Pilot” turns up a third time on Wham's “Freedom”. Scissor Sisters' “Take Your Mama Out” is practically a slowed-down “Saturday Night's All Right For Fighting”. He's all over US singers like Father John Misty and Ben Folds, the guitarist from the band Type-O Negative says he wanted to be a rocker after hearing it and I’m pretty sure the emo band Funeral For A Friend are named for the first track.

Where To Go From Here?

Elton has a pretty typical back catalogue quality graph for a sixties rocker who hung in there. He had a solid seventies, a horrendous eighties and (inter)national treasure nineties.

For the seventies you've got Elton (1970), feeling more authentically like the debut than the debut, Tumbleweed Connection 1970 in which Elton becomes one of the first artists to go country before visiting America, 17-11-70 (1971), a brilliant live album that gives you a taste of what that star-studded audience at the Troubadour must have heard. Then there's Honky Chateau (1972), his first dalliance with glam, good one, it's creatively all over the shop, but disciplined at ten tracks. Don't Shoot Me, I'm Only The Piano Player (1972) is good too, but it's a little obvious that he's heard Ziggy play guitar and is dead jealous. Post-Goodbye Yellow Brick Road, his second most famous effort is Captain Fantastic and the Brown Dirt Cowboy (1975), Elton's fav, with a Bosch by way of Crumb-looking cover, an album doubling as his autobiography.

I cannot stress enough how much of a motherfucker the eighties was for him. Digital production is not his friend and the ultra-divorced Jump Up! (1982), the Kenny Loggins lovin' Leather Jackets (1986) and unwanted end-credits song stylings of Sleeping With The Past (1989) are all fiascos. Two Low For Zero (1983), however was something. I feel he had discovered MTV in the way he had discovered glam and it yielded “I'm Still Standing” and “I Guess That's Why They Call It The Blues”. The nineties is when I, a passive music child, discovered him with the song “Made In England” from the album of the same name. I did not care for it one bit and nor do I now. It is one of those nineties hits that got played to death at the time but is never heard any more (the only comparable example I can think of is “Tell Me When” by The Human League). Made In England (1995) annoyed me further by containing “Belfast Child” a sincere ode to me that I have to say didn't resonate very well, but it's still a pretty interesting album if you want to study Britpop, going deeper than its indie surface.

This century, the highlights are probably his coming-out album Songs From The West Coast (2001), a series of duets with an old mentor on The Union (with Leon Russell) (2010) and The Diving Board (2013), a very focused and accusatory set of stomping ballads with nods to Bowie, Cohen and Brel.

For other musicians, maybe check the aforementioned Laura Nyro, Leon Russell and Marty Robbins.