At the top of my last article, an extended review of the Nine Inch Nails album The Downward Spiral, I mentioned the documentary Room 237 because I was worried that some of my deeper readings of NIN’s work could be ill-founded, hallucinatory, a product of loving the text too much.

After listening to and around a single album for a solid month, the mind starts to need breaks. I took a break. I tried to watch an unreznorly chill hang of a movie. I picked 1998’s The Big Lebowski. I watched it and enjoyed it, then got back to my Nine Inch Nails research.

It was at that point that I realised my error. The tiniest little dot caught my eye and it turned out to be a bowling ball. I watched it way too long. It was pulling me down.

Maslow’s Hammer had set in, and every problem, even a chill comedy, had started to look like Nine Inch Nails.

Ground Rules

I am about to write about the Coen Brothers’ 1998 film The Big Lebowski. In doing so I solemny swear to adhere to the following rules:

Don’t get lost. This article will be broken up into small chunks. Chronological order is impossible, but coherence might be possible.

Don’t constantly talk in movie quotes. Articles which do this are annoying, especially when you are reading lots of them for your own article.

Don’t suck the fun out of it. Not easy. I am talking about a comedy that does not give up all of its jokes easily. One of these is one of the most elaborate, expensive and disgusting dick jokes ever committed to film. If you would rather the movie serve you these jokes instead, with better timing, then go there repeatedly until successful. Otherwise, read on and I’ll do my best to keep you awake and entertained.

Nine Inch Nails?

Nine Inch Nails.

The Filmmakers

The Coen Brothers, writers, directors and editors of The Big Lebowski are thought of as auteurs. Their films can all be seen as comedies, of varying bleakness. They are stylised. They contrast purposeful, dynamically choreographed actions with clumsy expressions of human fallibility. Their films are often written chronologically on the first draft, page one to page final, no outline, lending them a certain spontaneity. They use a lot of offscreen time to tell their story, having key events happen in and around the outside of the audience’s vantage point. It is also documented that the brothers rewatch from a small collection of their own favourite films before diving into a new script. There is a lot of Americana onscreen, whose aesthetics are explored in sound, visuals and language. There are also high themes, crypticism, symbolism, references to other media. The Coens give their films distinct personalities, beginning at script level. That’s their schtick in a nutshell.

The Coens shooting scripts are adhered to strictly, giving actors very little agency to tamper with language. Take this monologue, delivered verbatim on screen:

Actors are used to convey words more or less exactly, sometimes down to the intonation, freeing them to focus solely on posture, gesture, movement, emotion.

Apart from the brothers themselves, their long-serving team of cinematographer Roger Deakins (Kundun, Skyfall, The Shawshank Redemption), composer Carter Burwell (Velvet Goldmine, Twilight, In Bruges) and music archivist T Bone Burnett (Cold Mountain, True Detective, Nashville [2012]) are the most influential creative figures on the films.

The Film

The Big Lebowski is I would guess the Coens most laboured-over script, certainly their most detailed. It’s a comedy up top, but its subgenre is quite fluid. It is thought of as a detective noir story, because all of the elements are there: Macguffins, femme-fatales, private dicks, double crosses, intense shadows and darkness. It is thought of as a stoner film, because all of the elements are there: drugs, counter-culture, tripping, squares, intense colours. The latter genre interests me more because it is not as often connected to film writing about The Big Lebowski, but for completeness sake, let’s recap the noir connection.

Two screen adaptations of Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe stories provide something to The Big Lebowski. The first is The Big Sleep (1946), a standout among the classics. The second is The Long Goodbye (1973), an aggressive New Hollywood twist on the form.

The Big Sleep

Opening scene is similar to The Dude’s visit to Lebowski Manor. Rich old man in a chair, buttled on, surrounded by brandy. The old man’s two daughters have a similar role to play as Bunny and Maude. The place is fancy, one of many idylls showcased throughout, including a playboy’s mansion, an orientalist boudoir, and a couple of really nice book emporiums. The Big Lebowski is similarly stuffed with idylls.

The Big Sleep has dames, about seven of ‘em flirting with the protagonist. The last one is Mona Mars, the Minnesota connection, played by Duluth’s own Peggy Knudsen, whose last name the Coens borrowed for Fawn. Elsewhere you’ve got important folks flanked by pairs of goons, a butler trying to reach the protagonist, and a “dick” who calls himself a “shamus”, with limitless access to alcohol everywhere he goes.

Honorable mention to Bogey’s other triumph The Maltese Falcon (1941) for giving the Coens the expression “suckin’ around”.

Honorable mention also to Murder My Sweet (1944) for the repeated knockouts and the line “There was no bottom”.

The Long Goodbye

Considerably more influential on The Big Lebowski is Robert Altman’s take on Chandler’s The Long Goodbye. While I like this film a lot, I am glad that it did not spawn its own religion. If you’ve seen it, you know why.

The Long Goodbye opens and closes on an oldie, in this case “Hooray For Hollywood” by Richard Whiting and Johnny Mercer, the latter of whom wrote the lyrics for the title song as well.

Most of the rest of its connection to The Big Lebowski is a grab bag of images and language. The protagonist has a bowling pin in his apartment, seen as a pair of officers interview him, one poking at his ashtray. It is situated between two globes, as it happens. One of the officers, wearing a peach-coloured shirt, lifts a heavy object and asks “what the hell is this?” before being sarcastically told it is a diminuitive object. There are nude women in the film, shot in the far distance. There is a dirty handprint on glass, as there is on Maude’s limo. There are dogs. They bark a lot. A woman with a posh accent takes the protagonist for a mark. The protagonist is told to make his own cocktail. There are cartoonish giant boors. “Do you see what happens?” happens, though not to a car. There are competing idylls. An ongoing misunderstanding about money involving a bag of laundry. Erev Shabbos is mentioned by the most dangerous person in the movie. The protagonist has a catchphrase. Someone asks what yoga is. A private dick is tailed by an inferior double. The protagonist is told he never went to college. Castration is threatened.

Elliot Gould’s Philip Marlowe is a very casual, wisecracking figure and a man out of time. His performance is interesting. He’s quite cartoonish. Some of his mutterings sound like Popeye the Sailor, which Altman would later adapt for screen. There is a person with health problems who can’t speak. He gifts his harmonica to Philip Marlowe. This seems to represent an important event in musical history, the gifting of (mute) Woody Guthrie’s harmonica, to Bob Dylan. All that Popeye talk starts to sound more like Bob Dylan after this, making the film feel like a transition from Guthrie’s America to Dylan’s.

This movie is a core text for the Coens. It’s made its mark on Fargo and Miller’s Crossing too.

Another unifying factor between these three films is the strange treatment of women in the story. Cases have been made that all three films are sexist in the extreme, for their time and for now. If they are, they are unconventional about it.

The Big Sleep exists in a world where every woman in focus is a well-dressed exciting young beauty, even the extras. Absence of children and elderly women isn’t unheard of in noir, but this movie has dozens of women, so it’s very noticeable.

The Long Goodbye has a complex about women the likes of which I have never seen anywhere else. It is scored more by sexism itself than it is by the music of John Williams. Women with men are under constant threat of violence. Women without men are treated as airheaded gaggles. The male protagonist says “it’s ok with me” every time he thinks about women.

It is well known that these are both Raymond Chandler adaptations. It is less well known that both were adapted for screen by the same woman, Leigh Brackett, the sci-fi and detective author who also wrote screenplays for The Alfred Hitchcock Hour, Rio Bravo and Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back. She was of course working with Howard Hawks and Robert Altman, so let’s not put the whole thing on her and Chandler.

The Big Lebowski has two women of agency, both of whom are sex-crazed dream girls. In the shooting script, Maude is nude through her entire first scene (perhaps an omission, perhaps the beginning of a haggling process over the actresses’ overall onscreen nudity). The rest of the women don’t have much story at all, with the younger ones dressed in a less glamorous fashion, perhaps to shine emphasis on the big two.

Stoner Films

Broadly, stoner films fall into two categories, films made with a nod to drug culture and films watched with a wink to drug culture. They include comedies like Up In Smoke, The Blues Brothers (all the drugs, so many drugs, were behind the camera on that one), Dazed and Confused. Such films share themes of musical nostalgia, cars, the joy and importance of silly conversation, serene protagonists besting an authoritarian opposing force, enjoying a taste of nirvana along the way. Films watched through the stoner lens often relate to these themes and include colorful fantasias, cartoons, exploitation cinema and moral panic information films.

The Dude Testament

In addition to being a stoner noir comedy, The Big Lebowski is a testament. All I really mean by this is that it contains lots and lots of information, some relating to profound topics: life, death, philosophy, psychology, ideology, religion, identity and culture. When you do this, and when your work is both a little resistant to analysis and deeply popular, then the thing that you have made becomes a sort of a gospel, and sets of people will start to treat it like one. Other things with these properties include Star Wars, Neon Genesis Evangelion,The Simpsons Seasons 1-9, Twin Peaks, Kingdom Hearts, Harry Potter, Metal Gear Solid, Steven Universe, The Rocky Horror Picture Show and Fight Club.

All of these texts are at least enough of a cult that we can assume someone has themed a wedding around them. Maybe not Fight Club, due to the demographic it attracts (EDIT: I checked and Fight Club-themed bridal showers are a plot point in Bridesmaids). Dudeism, the “religion” based on The Big Lebowski exists partially because of this doctrinal quality, but there are other factors.

I said that The Big Lebowski is resistant to analysis. It also demands it. The protagonist, The Dude, is an ostensibly relaxed person. He relaxes in his first scene of the movie and his last. However his relaxation is interrupted in every remaining scene of the film, by peril, conflict, information, “new shit”. As the viewer is with him, they too are interrupted. Their participation is needed. This continuing need for engagement is further emphasised by the character of Donny, who isn't keeping up with his Polish-American intellectual friends, and who is thoroughly admonished for this. Keep up.

Donny is a surrogate for the slower members of the audience. He acts like he’s in a story about bowling. On landing his first strike he asks The Dude to “mark it”. The Dude is too busy. Donny gets his pen out. He has to keep score himself. Keep up.

Assuming the viewers desired state of receptiveness, the Coens take this state and abuse it to play with the viewer. They use signifiers of many kinds at a frequency that cannot be processed. It is impossible to parse every line of dialogue in a viewing of The Big Lebowski, not just because there is lots of it and it is frequently fast, overlapped. It’s impossible because of the amount of information coming at you in dialogue, set design, props, costume, casting, colour, light, sound, in references to artworks, films, songs, religions.

Some of the information furthers the plot. Some of it is irrelevant to the plot. Some of it is irrelevant to the plot, but invites the viewer to read into it anyway.

The pertinent, non-pertinent and “anti-pertinence” nature of the information is routinely commented upon by the film and its characters, many of whom are also unreliable narrators. Here are some of those commentaries:

In the opening, The Stranger (the narrator who himself is an unreliable narrator) describes the story we are about to see as “stupefying”. Later, Maude Lebowski turns away from Logjammin' and into the camera to say “The story is ludicrous”. Later she asks “What do you think this has all been about?”. Walter pronounces that “The chinaman isn't the issue here! (Also, Dude, “chinaman” is not the preferred nomenclature. Asian-American, please)” and the Big Lebowski shouts “My wife is not the issue!” (launching a magnifying glass as he does so), adding “I cannot solve your problems sir, only you can.”. The Dude asks “What about the toe?” Walter says “Forget about the fucking toe!”. He soon does. Walter asks “Am I wrong?” nine times. The answer to those nine questions as given by characters and audience will differ, with the conclusion being “sometimes”.

The ideal audience is being conditioned to “keep up”. But with what? On first viewing, maybe it’s the clues:

Take the severed toe, Larry Sellers homework, the Treehorn sketch. The toe leads to the solution to the kidnapping, were a 1991 criminal forensics team looking at it, but for both The Dude and the audience it’s a solution which arrives too late. Absurdly, the audience are given a big hint about the toe when the nihilists order lingonberry pancakes and pigs in blankets, a visual representation of a toe in a bloody wrap of gauze. This occurs exactly two seconds before the solution of the toe’s owner is revealed to the audience. The Dude doesn’t hear about the toe until the fight outside the bowling alley, at which point it is of no material consequence.

Larry’s homework serves only to cost The Dude more car parts. The Treehorn sketch serves only to make him look a fool in front of the Malibu Police, a mission already accomplished. The movie laughs off the very notion of clues when The Dude asks the officer presenting him with his recovered car if he has any “leads”. The moment The Dude refers to the events of the film as a “case”, he meets a ridiculous detective who challenges his own identity as detective, and his pacifism to boot.

There are further clues, outside of the protagonist’s hands. For example, The Dude and Walter both suffer from a curious inability to identify mammals. Walter presents his dog as a probable Pomeranian, when it is a Yorkie. The Dude goes along with it. When The Dude sees a ferret he says “nice marmot”. Walter further misidentifies the beast as an “amphibious rodent”, which neither a ferret nor a marmot are. This tells the audience that Bunny is misidentified, her real name turning out to be Fawn.

In summation, although we are repeatedly commanded to engage mentally, the up-top narrative of The Big Lebowski is an unserious one. Beneath this however is something of a join the dots puzzle, with multiple solutions and too many damn dots. It is a detective’s corkboard, with enough string on it to reach the moon. It is a starfield, begging for constellations. We’ll get to the Nine Inch Nails constellation shortly, but first:

Stanley Kubrick

In their film Barton Fink, the Coen Brothers make reference to Kubrick’s The Shining, using steadicam shots to unsettle in the hallways of a hotel. In Raising Arizona, the grafitti “POE-OPE” is seen, a nod to Dr. Strangelove. In Intolerable Cruelty, Herb's medical equipment makes sounds from 2001: A Space Odyssey. In The Hudsucker Proxy, Khachaturian’s ballet Spartacus is a primary theme of score and plot. In Fargo, there is a reference to A Clockwork Orange as a character says he's in town for "just a little of the ol' in-and-out", as well as many references to The Shining (bathroom escape, frozen man in maroon, the final murder, itself reprised twice in Burn After Reading).

There are three distinct Kubrick references in The Big Lebowski. When we see the character Bunny, she is framed as though she were the title character of Kubrick’s Lolita.

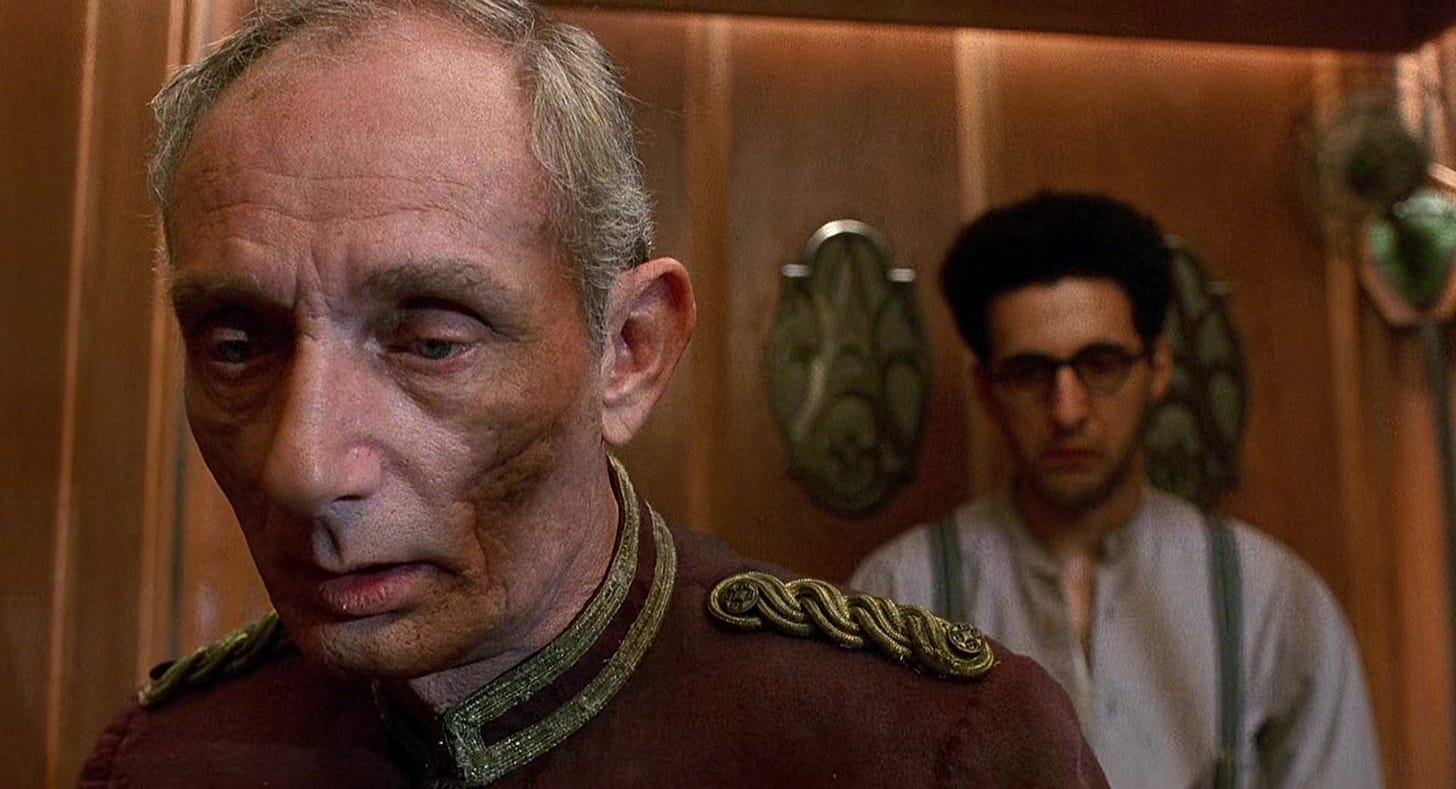

When the Malibu Police Chief gets physical with The Dude, he becomes the drill sergeant from Full Metal Jacket.

Any major Kubrick fan would spot these references, but the third takes a little more unpacking.

In Fargo, Carl (Steve Buscemi) and Geaer (Peter Stormare) play partners in crime on the road. Carl is a blabbermouth. Geaer is terrifying. The casting of The Big Lebowski inverts this. Buscemi’s character Donny can’t get a word in and Stormare’s Uli / Karl / Nihilist #1 is a character that no-one could fear by the film’s end, even as he wields a bladed weapon and threatens to castrate with it.

In Fargo, even as Gaear (Stormare) requests that he and Carl stop for pancakes, it is terrifying because it reveals him to be selfish, controlling, impulsive and volatile. Gaear gets his pancakes. Carl (Buscemi) gets"just a little of the ol' in-and-out".

In The Big Lebowski, Uli (Stormare) gets his pancakes (lingonberry pancakes). Donny (Buscemi) is insistent upon getting In-And-Out Burger.

The three Kubrick references form a comic rule of threes. We get the Donny one last (in spite of The Dude alerting us multiple times to there being “Lotta ins, lotta outs”) and we go “ah-ha!”, admiring the wit of it and patting ourselves on the back for being so smart.

David Lynch

David Lynch is another filmmaker that The Coens have referenced on screen: Eraserhead in Barton Fink (hair), Blue Velvet in Burn After Reading (wardrobe), Blue Velvet in Raising Arizona (sweet dream), Mulholland Drive in Intolerable Cruelty (pool boy, swervy driving). Lynch (with his writing partners) is an expert in constructing intricate works of semantic tension, intensely deep plots, open interpretation of events. Worlds and stories that often reward detective and intuitive reasoning. Lynch says relatively little on the construction of his films, and almost nothing on their intentions, but describes the creative process as “You feel-think your way through”.

Nine Inch Nails

In the mid-nineties, Nine Inch Nails had two albums, both quite famous, the first being Pretty Hate Machine (1989). A handful of famous songs too: “Head Like A Hole”, “Closer”, “Hurt”. Their aggressive, technology-driven music was often categorised as “industrial”, their dark lyrics as “nihilistic”, though neither of those tags are a neat fit in practice. Frontman Trent Reznor caused quite a stir by moving into the Hollywood house where Sharon Tate was murdered. It was there he recorded The Downward Spiral (1994), an album about a man’s total ruination through sin and temptation. Reznor would also collaborate with David Lynch for his film Lost Highway, a soundtrack featuring contributions from Rammstein and Marilyn Manson. These musical artists all pushed the boundaries of good taste in lyrics, visuals and by being aesthetically extreme. This is about all you need to know about them for this article.

I realised watching The Big Lebowski for the first time in a while that there might be a reference to the band, maybe more than one reference. I can’t be sure, but there are sensical reasons why this would be the case.

The Reasons

I don't know a lot about the Coen Brothers own musical tastes, but from their film soundtracks I have them down as avid music listeners. Avid that is up until the rise of synthesis, lets say the late seventies. The Dude and his bowling team are living in the past, either Vietnam (Walter), the last thing anyone said (The Dude) or having missed the last thing anyone said (Donny). The Coens are living in the past too, their movies are all set in the past or situated remotely enough that the present is close to irrelevant. A crucial thing to bear in mind is that the Coens differ from peers Tarantino and Lynch in that they do not always populate their films solely with the music that they enjoy. Like their peer David Cronenberg, they will break out music they don’t like in service of the story, if needs be, in conjunction with their in-house composer and music-getter.

SCENARIO ONE [DEBUNKED]

Supposing you are the Coen Brothers. You’ve heard that your fellow traveller in film, David Lynch has a new film in the can. Great! It also seems to be named for a quaint song by one of your favourite singing cowboys, Hank Williams, father of country music, whose American warmth you return to again and again on film. Great! You attend the premiere, but something is off. You don’t care for the film as much as the rest of Lynch’s ouvre (putting Dune to one side). The premiere itself is weird. It’s dark. There’s too much noisy modern music, black leather, tattoos, goatees, Satanists, skinheads, Germans, just enough to subtly ping your antisemitism radar. Zero country music too, what a letdown. The fellow you’re stuck sitting behind during the screening is 6’6, blond and he’s wearing a vintage German biker helmet and tiny sunglasses.

The debunk: The higher-profile premieres of Lost Highway, including the one attended by Rammstein took place during the shooting schedule of The Big Lebowski.

SCENARIO TWO

Maybe the Coens get to see Lost Highway in advance of its premiere. The film was shot in 1995 after all. Maybe they merely have a conversation with Lynch about it, or read industry press. Perhaps they are a little bewildered that their 50s throwback friend is going so modern on the music again, so they get curious and start reading about some of the musicians in question: Nihilistic this? Neitzsche that? Nothing Records? Das Modell? Shocking. Might be time to send a message to your comrade, and beyond, that good music is under threat from computers, apparent neo-pseudo-crypto-fascism, the spectre of “industrial”. The machine, man! And wouldn’t it be exciting to bury that message deep in the inner workings of an already stuffed film, to be excavated at a later date?

Between them, the Brothers brainstorm a funny idea, a band who are not merely characterised as nihilistic but who are actual nihilists, who can't stop saying that they believe in “nassing” and that they want to “fuck you” (“like an animal” implied, with the diminuitive marmot, later substituted with a ferret, as the animal). They get help from the costume department, who kit the boys out in worksuits, biker gear and helmets a la Rammstein, and from soundtrack composer Carter Burwell, who knows a thing or two about industrial music, having released work on Factory Records in the eighties.

SCENARIO THREE

You are the Coen Brothers. You make The Big Lebowski. At no stage do Nine Inch Nails, Rammstein or Lost Highway even cross your mind.

Scenario One is impossible. Scenarios Two and Three, or some midpoint are possible.

Get To The References

Okie Dokie.

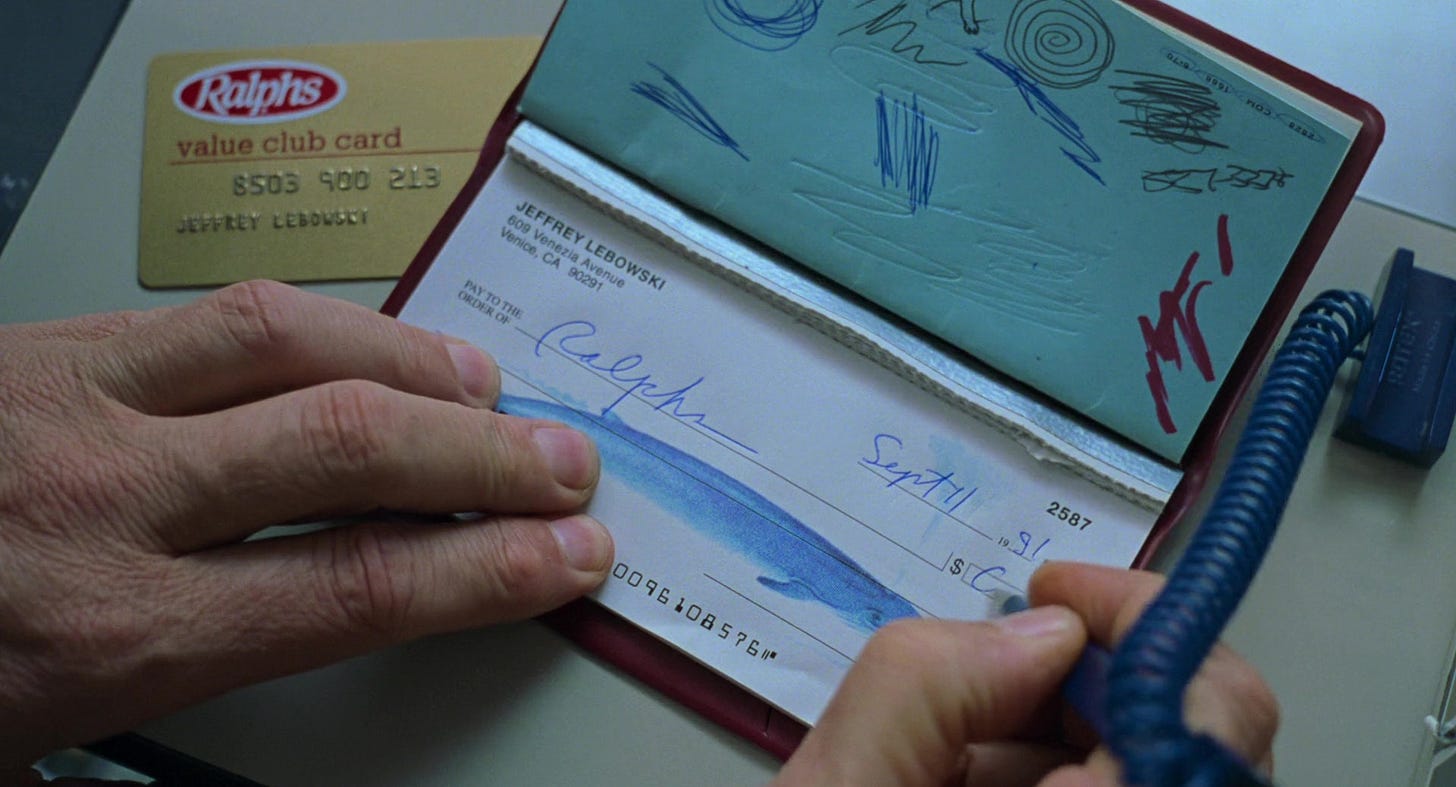

The Spiral

That’s it? That’s my opening gambit? A squiggle at the top of the frame?

To answer your first question, no, frontal lobe complications do not run in my family.

The spiral is a fairly widely understood symbol in the West. It represents on one hand hypnosis: spirals are used in films as hypnotising agents. Spirals are also groovy and psychedelic: one can picture them on the skin of a bass drum of a 60s band with go-go dancers, on a lollipop inWilly Wonka And The Chocolate Factory, and in the visual geometry of LSD trips. Spirals can also represent a sort of out-of-control momentum, as in Hitchcock’s motifs and Saul Bass’ artwork forVertigo. A downward spiral. I note that the term “downward spiral” appears in The Hudsucker Proxy, a film released too early for it to have been influenced by The Downward Spiral.

Indulge me though. The Downward Spiral is an album about a man who loses it all, with a lot of sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll along the way. It ends with profound irresolution, both musically and with a lingering question about the fate of its protagonist. The Big Lebowski is a film about a man who indulges in sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll. He is tortured (literally), beaten, his worldly possessions and sanctuary are defiled and ultimately ruined. It ends with profound irresolution, both musically and with a lingering question about the fate of its protagonist.

“World Of Pain”

In two different scenarios (involving Smokey and Larry), Walter uses the expression “You’re entering a world of pain”, following both uses through with threatening behaviour. I have searched the etymology of this expression and I cannot find it used before The Big Lebowski. The expression existed long before, but as “world of hurt”. “Hurt” is a Nine Inch Nails song.

To answer your second question, yes, these references do get a little stronger as they go.

The Nail Boards

The Big Lebowski has a lot of nails in it. The Dude and his gang can be represented by his board with nails hammered into it, downwards, sloppily. The Nihilists can be represented by a board with nails hammered into it, upwards, efficiently. The imprecision of rock against the quantisation of techno-pop.

Just as Uli nails Bunny, The Dude is nailed by Maude. He lets her violate him.

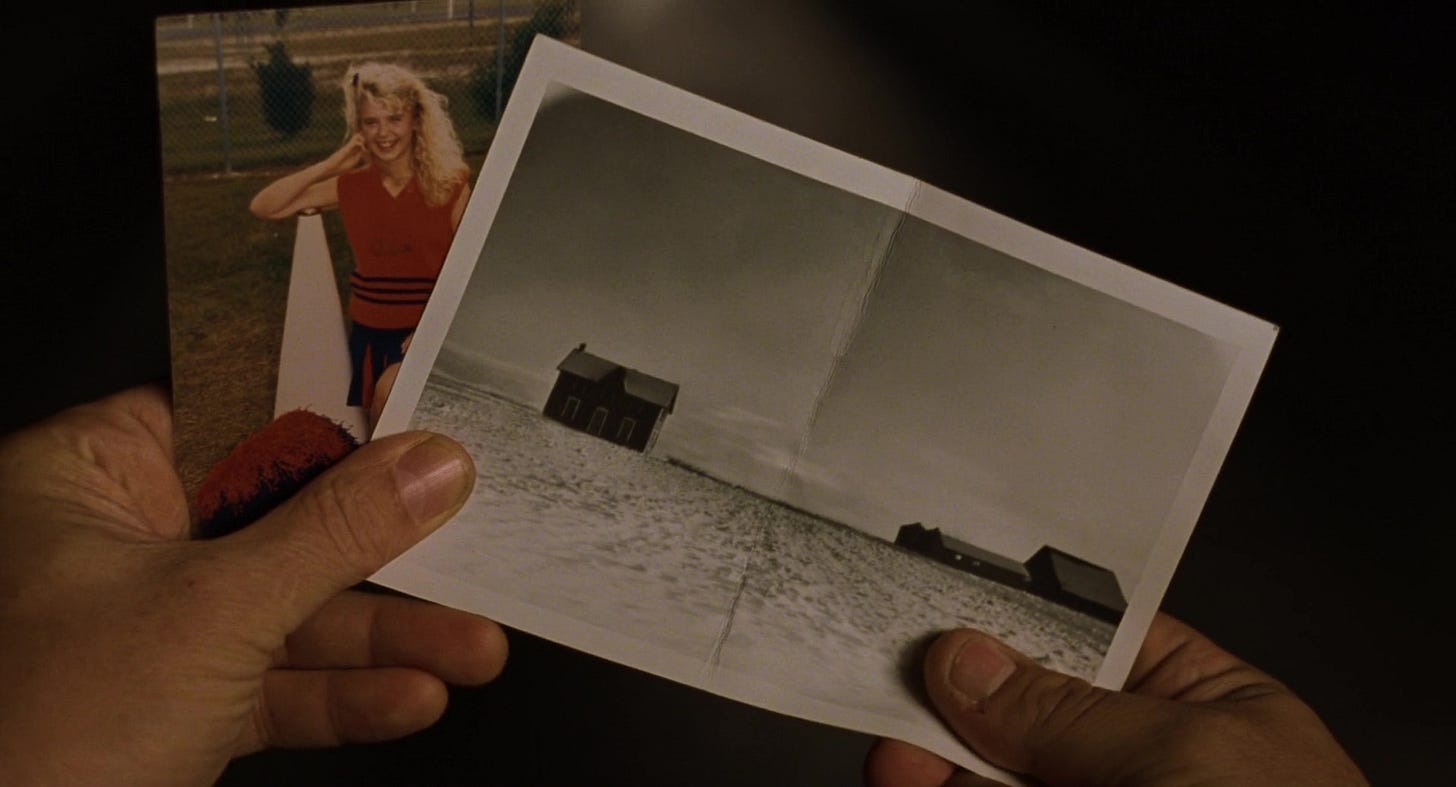

Nine Nails

Bunny paints her nails, The Jesus paints his nails. Near the end of the film, The Dude paints his nails, highlighting ‘nails’ as a theme, notably after it bears any relevance to the identity of the severed toe. Bunny, Jesus Quintana and the Nihilist's girlfriend are all seen with nine nails. In the case of Bunny, the Coens have commented that they willfully shot the sequence of Bunny in her car with a shadow cast across her all-important tenth toe to promote a splitting of understanding in audiences watching for the first time. It worked, lots of first time viewers think that she is missing a toe. In the case of Jesus Quintana, he has painted one of his fingernails the colour of the toecap on his shoes. One of his nails is always removed from view by his bowling support glove.

The Coens did an interview for this movie with Bobbie Wygant, in which they cannot stop fiddling with their nails, to the point where I wonder if it is deliberate.

The LP

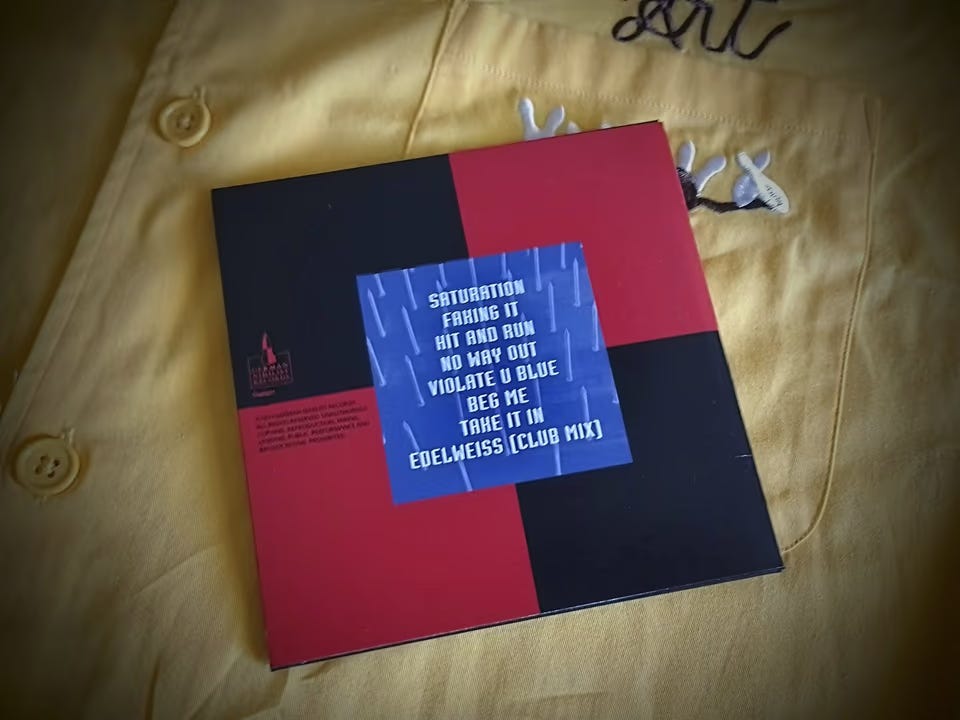

Enter the fictional “Ugh. Sort of a techno-pop” band, Autobahn, who in the movie released a solitary album in the late seventies before ambling on with the times. Looking at the cover of this album we are met with a double-header of Kraftwerk, the covers of Autobahn (1974) and Die Mensch·Maschine (1978) mashed up into something very silly.

Silly because one of them is absurdly tall Torsten Voges (who went on to play Tina in Deuce Bigalow: Male Gigolo, his head omitted from frame, to repeated shouts of “That’s a huge bitch!”). Silly because one of them is Flea, an actor/Chilli Pepper famously typecast as an outsized comical punk. Silly because one of them is named Uli Kunkel aka “Karl Hungus”, and because they all talk like perverted Eurotrash dandies, and because their ferret is dressed in kinky studded leather.

I saw this movie when I was thirteen, I didn’t confuse the Nihilists for a Kraftwerk analogue then and I don’t now. Rather, this cover speaks to the vacuity of the band, whose influences are evidently Kraftwerk and Kraftwerk, in Germany, in the late seventies. No ideas of their own. Living in the past.

Why would an LP from the late seventies have anything to do with Nine Inch Nails? The Coens seemingly don't listen to synth pop or industrial or techno or pop of this sort (“techno pop” is not a genre, at least not in the parlance of the late seventies). The two seem broadly dismissive of electronic music, maybe it’s all the same to them, the machine, man.

Look again at the cover, there are nails galore, and the title is Nagelbett (“Bed of Nails”). What about the back? The tracklisting of the Nagelbett album, briefly visible over Knox Harrington’s scouse laughter, confirms the assertion that Autobahn are empty-headed past-dwellers, with second-hand hackneyed track titles: “Saturation”, “Faking It”, “Hit and Run”, “No Way Out”, “Beg Me” and “Take It In”.

A question of intentionality occurs here, i.e was this dreamed up by the props department or the Coen Brothers? As we are dealing here with music, the films composer Carter Burwell and music archivist T Bone Burnett may also be in play along with any relevant production staff. Let's look at the remaining two track titles. The first is “Edelweiss (Club Mix)”. “Edelweiss” means “pure white”, sounds like an aryan dream. It is also a song from The Sound of Music, an ode to the Motherland (Austria). I feel that’s a gag pithy enough that the Coens wrote or approved it. After all, what would a “techno pop” outfit care about Rodgers and Hammerstein? If only the Coens were more invested in industrial music, they would have realised that it too can have a sardonic sense of humour:

The name of the remaining track is “Violate U Blue” and the first line of “Closer” by Nine Inch Nails remains “You let me violate you”.

Jack Kehler

Jack Kehler is the only actor in this movie who is also in Lost Highway, his main line in that film echoing the Coens hypothetical review of it. He plays The Dude's landlord Marty.

The Coens for their own amusement tasked him with coming up with an undignified, idiotic dance routine, leaving him alone for several days to come up with the goods. Was their treatment of Kehler or his character itself an abstracted slight against Lost Highway?

Like Jesus Quintana and Uli Kunkel, Marty is a figure of fun, both in and out of his costume:

“The Jesus” is introduced utterly suave in costume (to the hated Eagles) and then promptly defrocked, Walter’s accusations real enough to merit a scene of him out of costume, degrading himself by (not yet enacted) Hollywood law.

With Uli, the first time we see him, he is out of costume, asleep, intoxicated, jaw agog. He is working on his tan, a joke in itself as we later find out he is nocturnal, on German time. All of his other outfits are no less imbecilic, with one exception:

The T-Shirt

On now to the final conflict with The Nihilists. How did we get here?

The Dude is comfortable with all music, except The Eagles. He can even dig notorious mellow-harshers Metallica, enough to be their roadie, even if he thought they themselves were a “bunch of assholes”. Note that real-life Dude Jeff Dowd was never a roadie for Metallica, but he did go on to be the marketing executive for Metallica’s Some Kind of Monster (2004). Even techno pop doesn’t offend The Dude. Rather, techno pop announces itself as The Dude’s enemy, goes after him, attacks his own musical tastes. When Autobahn enter his apartment, the first thing that they do is demolish his beautiful-looking 1970s hi-fi stereo setup. When we see them at the end, they have ignited his car, destroying his eight-track tape deck and his beloved Creedence, playing their own music out of an inferior 90s compact boombox. Musical warfare.

At the end of The Big Lebowski, the Coens’ gang of loveable bowlers face off against Lynch’s (by insinuation) suffocating rubber clown suits of negativity. Aimee Mann plays the girlfriend who gave up her toe. Fitting, as she is someone who abandoned the trappings of “techno pop” (variously as a member of Ministry and ‘Til Tuesday) in favour of simpler solo songwriting, to great success.

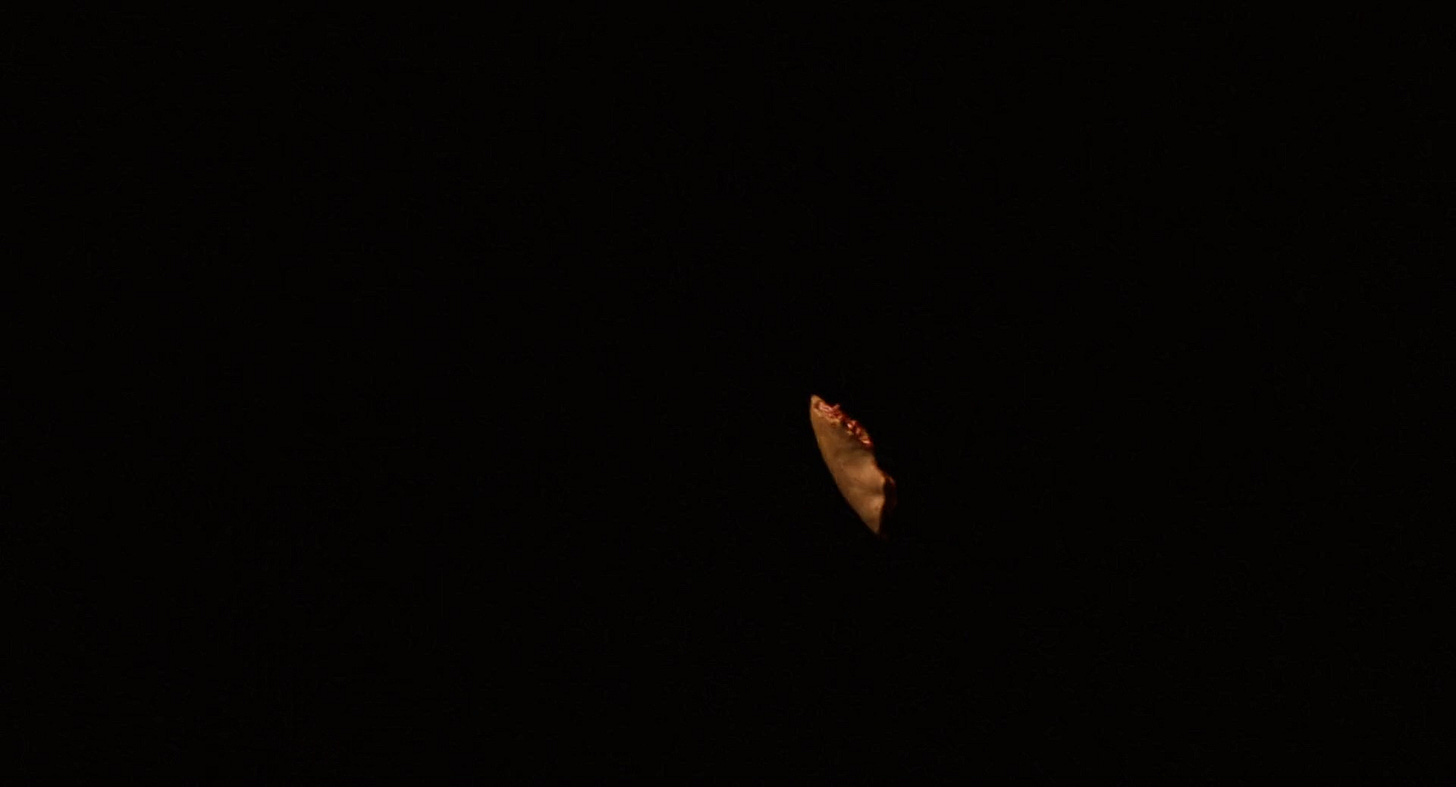

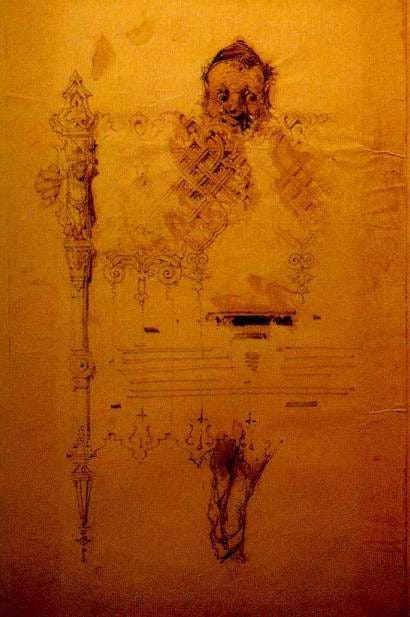

Consider Uli’s T-shirt in the image below:

It’s an abstract image, red on black. Nine horizontal lines, with more pronounced spaces between lines one and two, four and five, five and six, eight and nine. Lines three and seven are the thickest. How would such an image be produced? Tie-dying? Screen printing? Photocopier dragging? What would one use as a source image? Would this work?

Who knows. Also, when you want David Lynch’s ear, a good way to go about it is to have a man lose his right ear. Tarantino knew that too.

“Wie Glauben”

The Nihilists have written a musical manifesto which they foist on their prey. It is “Technopop (Wie Glauben)”, composed by Carter Burwell. “Wie Glauben” follows an interesting brief. It has to play at cinema size, so it is wide and high fidelity. It has to score a fight scene, one that has been shot and edited for comic timing, something which has its own rhythm. Consequently the beat does not roll, pump or get going the way club music usually does, leaving space for Walter to be the main percussionist.

“Wie Glauben” also has to speak to who The Nihilists are. It does this lyrically, with variations of “We believe in nassing” in English and German. It also does it through pastiche. Undoubtedly Kraftwerk are the primary influence, not a specific song, just the band’s essence. In addition to bilingual lyrics, there are vocoders, clinical synths, electro drum patterns, “laser” sounds as percussion, and a composition which stays in a single groove throughout. For a song accompanying the destruction of a car it sounds more like a piece of music for a transport expo.

Does it have any sonic commonalities with Nine Inch Nails? Arguably. The “string” section at the start bears some timbral resemblence to the “choir” part of “Closer”, the percussion has a density of sixteenth notes, a technique rarely employed by Kraftwerk, but certainly by Nine Inch Nails in “Head Like A Hole”. The upper bassline is probably a commercially available subtractive synth like NIN’s favoured Minimoog and ascends a scale on the groove notes only, a technique used throughout electronic body music, but also on “Closer (To God)” and “Happiness In Slavery”. In other words, it’s a bit of a stretch.

Nagelbett isn't a real album but at least two small artists have recorded their own interpretation of it in tribute, both consciously using NIN signifiers in the music.

Heads Like Holes

In his battle against The Nihilists, Walter proceeds to give each of The Nihilists a “head like a hole”. Flea is first, getting a bowling ball to the gut, showing his “o-face” and rendering him unable to talk. Then it’s Stormare’s turn, he gets a more literal hole in the head as his ear is bitten off. Finally it’s the turn of Vorges, who gets a stereo smashed in his bespectacled face, leading to a frame or two where he has a hole for a head.

Closer (To Jesus)

This was the shot that sent me down this stupid bunny hole. A man with long black hair and shiny black gloves licking an inanimate object in a close-up, left-to-right composition. If actor John Turturro didn’t realise at the time that these two shots were very similar, it is highly likely that he has realised since. The most famous line of the song “Closer” is “I wanna fuck you like an animal”. In 2019, Turturro starred in The Jesus Rolls, a non-canonical spin-off of The Big Lebowski centred on his Jesus Quintana character. The last line of the trailer, spoken by the title character is “I wanna hold you like a bowling ball”.

Afterwards

After the Coens made The Big Lebowski, they made O Brother Where Art Thou?, their most pervasive musical statement. Every other parent in a Christian household got that soundtrack for Christmas. As it happens, the soundtrack was the first release on a brand new record label, Lost Highway Records. The record label lasted twelve years until absorbed by its parent company Universal Music Group. Until 2025, when it came back, helmed by… T Bone Burnett.

David Lynch expressed great admiration for ear-removers Tarantino and the Coen Brothers and payed tribute to them in his own way in Twin Peaks: The Return. Tarantino’s work is represented by his own players Tim Roth and Jennifer Jason Leigh, as a cool couple who talk about snacks a lot before being blown away gorily. The Coens influence was less easily pinned down, but the screwball action and plotting of Dougie’s days at Lucky 7 Insurance, the many misunderstandings in South Dakota in the season premiere as well as the dull-witted musings about, as in The Big Lebowski, the importance of a bunny, definitely feel informed by them. Also Twin Peaks: The Return used the final song on the soundtrack of The Big Lebowski, Shawn Colvin’s cover of “Viva Las Vegas”.

Bowling alley Hollywood Star Lanes shuttered in 2002.

Lost Highway star Bill Pullman starred alongside Ben Stiller as a slovenly detective in the film Zero Effect. You might think that a film you’ve never heard of with that caliber of acting talent would be bad. In this case, you’d be right. It came out three months after The Big Lebowski, itself a box office underperformer, and was an even bigger flop. All was not lost, as writer-director Jake Kasdan went on to give us Walk Hard: The Dewey Cox Story, easily the funniest film ever written about “Hurt” by Nine Inch Nails.

At the time of writing this piece, Nine Inch Nails next record will be a soundtrack for Tron: Ares, starring Jeff Bridges.

After recording The Downward Spiral, Trent Reznor relocated to Nothing Studios, New Orleans to work on the follow-up, The Fragile before moving back to Los Angeles. The next person to move into his New Orleans house was actor John Goodman:

What did we learn?

The web I have drawn above is very pleasing, at least to me. Regardless of any filmmaking intentionality it points to, it is a proof of the strength of the gospel-like qualities of The Big Lebowski. Were someone offered a job to come up with a magazine column or a ‘thought for the day’ on this film, one could, indefinitely, for centuries, not least because the act of tracing patterns on the movie’s starfield can be very pleasurable.

How many US Presidents are in the movie? I count Lincoln, Roosevelt, Nixon, Ford, Johnson, Reagan, Bush, plus whomever’s on the money. How many mammals? How many hats? How many dick jokes? What, if anything, might those things mean, inside and outside of the story and the film?

To reach more deeply into a reading of The Big Lebowski, it would be wise perhaps to move on from music that isn’t in the film and look more closely at music that is.

PART TWO OF TWO

The Big Lebowski: A Musical Analysis

The Big Lebowski is often read in a way that totally excludes its soundtrack. There are hundreds of offenders, many of them film academics. This is a mistake, given how much of the information in the movie is musical. A Dude quote I haven’t seen on too many t-shirts is “Why don’t you fucking listen occasionally, you might learn something.”.

Here’s the thing about music. Music is usually supposed to be telling the truth in films. It’s really hard to make music into an unreliable narrator in a way that the audience can process. It’s just one of those things, like a “flash forward”. You can’t do a flash forward unless you explain the hell out of it, because otherwise the audience will assume it’s a flashback. Music can be used to convey doubt or parody, to make weak footage seem cooler or innocuous footage more ominous but those things are directly tied to the intentions of the filmmakers.

When The Coens took this film out on the road, they brought with them their music archivist to field questions, not a political historian, a Jungian psychotherapist or a priest. Has to count for something.

The Big Lebowski is a film where, surrounded by liars, we can count on the music to tell us the story as intended. I may not be equipped to analyze the film entirely, but I can at least offer below an interpretation of the significance, intentional and otherwise, of the music in the film. Along the way I will offer a few other things that I and others have noticed across many viewings, including of course one of the most elaborate, expensive and disgusting dick jokes ever committed to film.

In doing this article I have come to see The Big Lebowski as a study in comic form, an act of preservation and a thesis on cultural trajectory:

A Study In Comic Form

It’s a house of high and low humour, secret and obvious. It contains jokes with long fuses, jokes that require education, jokes that play with how jokes work. Not all of the humour is jokes-based, some of it is physical, some auditory, some visual, some musical.

An Act Of Preservation

In the novel Return of the Native, writer Thomas Hardy has a protagonist who is a reddleman. The job of a reddleman is to sell reddle, red ochre, a dye for marking sheep. Often reddlemen were red men, their exposure to reddle relative to soap making it so. Why write about reddlemen? Because they are an interesting phenomenon, and one not likely to last. The Coens are doing something similar with The Dude and Walter here. A pacifist of and a veteran of an extremely culture-laden conflict. One is still at war, Walter (based on John Milnius). One is still at peace, The Dude (based on John Dowd). Their attributes are highly influenced by their unique generational experiences and while there exists a period in history where everyone feels they know a Dude or a Walter, this will not always be the case.

The same can be said for many different things in The Big Lebowski, a film full of modern things which are seen to be on their way out.

A Thesis On Cultural Trajectory

Sounds lofty. All I’m saying is that The Big Lebowski looks at culture in great detail; golden things to be preserved, dead ends and where we’re all headed.

The Musical Cues of The Big Lebowski

Jerry Goldsmith - “Universal Pictures Fanfare” (1997)

Note: Depending on how you saw this film, you mightn’t have seen this ident. The film was released during the acquisition by Universal Music Group of Working Title and Polygram.

At the time of making the film, this piece of music is but one year old. It was first heard before Spielberg’s Jurassic Park: The Lost World to unveil Universal’s tacky new CGI logo, which overcompensated for the muted colours of prior iterations by dolling up our planet with saturated huebeams.

The music springs from a couple of notes of the 1934 Universal fanfare by Jimmy McHugh, and has a timeless quality. If you are sure the jingle is older than that, you are not alone.

Universal are notoriously open to filmmakers tinkering with this logo and fanfare (The Flintstones: Viva Rock Vegas, Scott Pilgrim vs. The World, Minions). I feel that the juxtaposition of old and new, tacky and timeless is why this logo was left unchanged by the Coens. One look at the font choices below tells you it’s on theme.

Sons Of The Pioneers & Roy Rogers - “Tumbling Tumbleweeds” (1946)

The Sons Of The Pioneers are a vocal group who are still active in 2025, nearing their centennial. They were once fronted by Roy Rogers, the King of the Cowboys. The cowboy is a recurrent figure in the Coens work. More often the Coens favour a fancier more Hollywood sort of cowboy, one who does dressage, has a hat that’s big, spins his guns, drinks milk. RR is one of their favourites along with Hank Williams and Gene Autry.

In his first screen appearance, Roy Rogers sang “Way Out There”, which would become the theme of Raising Arizona in the hands of Carter Burwell.

In The Big Lebowski, “Tumbling Tumbleweeds” heralds the coming of The Stranger, a talking tumbleweed for all we know thusfar, to tell us about The Dude. It speaks to the mythical qualities specific to The Stranger and The Dude: placidity, personal freedom, freewheeling, imperturbability.

Roy Rogers died five weeks after The Big Lebowski was released. End of an era. Wouldn’t it be something if he got to see it.

[reference] [traditional] - “I See Paris, I See France”

“I see London, I see France, I can see your underpants” - Nursery rhyme

“Course, I can't say I seen London, and I never been to France, and I ain't never seen no queen in her damn undies as the fella says.” - The Stranger

This oft-sung nursery rhyme helps make The Stranger’s opening monologue all the sillier. It establishes him as digression prone, loose of memory. Moreover, it foreshadows The Dude’s second journey down the bowling alley of love, where he sees his fill of underpants.

The Stranger’s interpretation of the rhyme also shares something with that of the private detective in the introduction of Blood Simple:

“Now I don't care if you're the Pope of Rome, President of the United States or Man of the Year; somethin' can all go wrong.” - Loren Visser

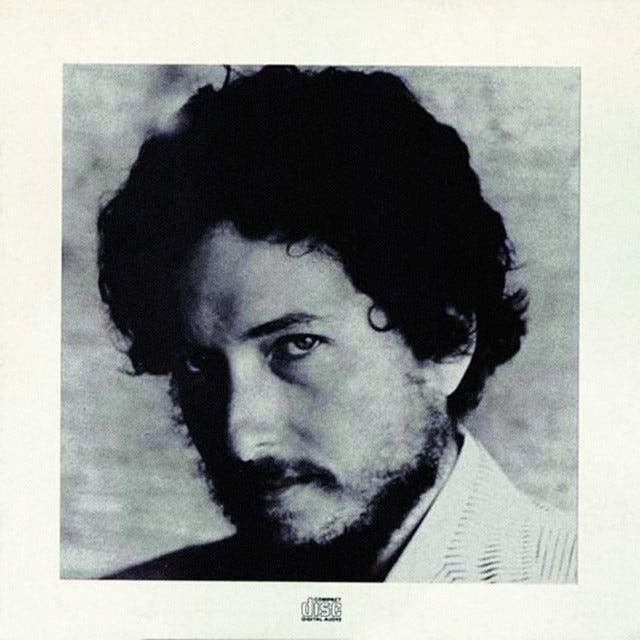

Bob Dylan - “The Man In Me” (1970)

The Coen Brothers are immense Dylan fans. They receive nourishment from his breadth of musical ideas, his poetry, his handle on the form of song and his personality as it exists in musical form.

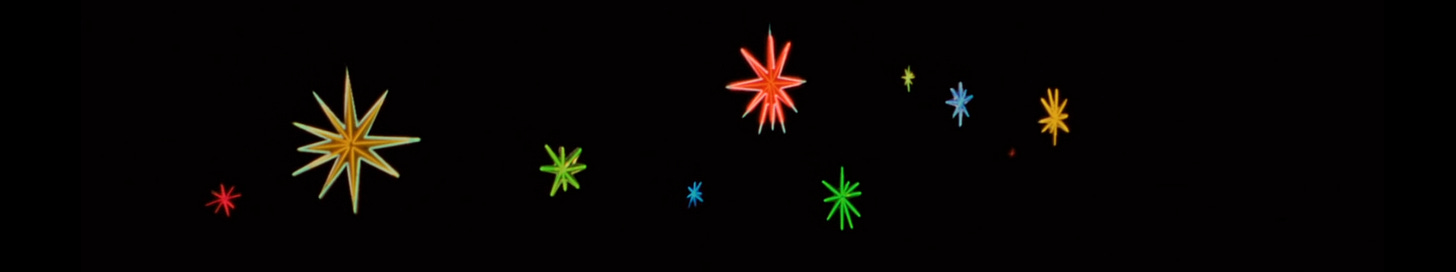

The first thing that strikes us about this song is its enveloping cosiness. Cosy too are the visuals, the oddly satisfying crafts and actions of a finely-tuned bowling alley. Ornate bowling balls, polished lanes, neon stars, ordinary people living in harmony, as though the global peace movement had gotten its way. Bowling as it was, back in the Golden Age of Bowling.

Bowling is historically working class, and a pastime favoured by Polish-Americans. “Poles bowl”, reads the stereotype. The Dude’s Polish last name is allegedly derived from Jeff Lebowski, the Assistant Attorney General to Minnesota.

Dylan was on a swing away from the political and into the self when he made this record. He was once thought the voice of a generation, part of a profound and unified cry for peace and justice, the positive ramifications of which cannot be measured. The Dude existed in this movement when he was an uncompromising member of the Students for a Democratic Society, co-author of the first draft of the Port Huron Statement, not the compromised second draft. Like Dylan in this period, this manifesto is said to be torn between advocating for community and for individuality, a perceived core problem for leftists to this day.

In this song, Dylan is self-interested, looking to chill and defend his abode:

“Storm clouds are raging all around my door /

I think to myself I might not take it any more”

The Dude’s doorway is of course a focal point for his own troubles, crossed five times by home invaders who gradually destroy his sanctuary.

“The man in me will hide sometimes to keep from bein' seen /

But that's just because he doesn't wanna turn into some machine”

Seeing as we’ve mentioned machines, let’s get into The Dude’s relationship with technology. He digs his car, a 1973 Ford Gran Torino, his tape deck, his hi-fi, his Sony Auto-Reverse Walkman. He owns a reasonable sized television for ‘91. He digs bowling. All artifacts which attained a kind of perfection in their day, to be replaced with tackier, worse things down the line. The Dude fetishizes this technology, to the point where it seems to inform his sexual fantasies. He is rather Ballardian in that respect.

SILENCE 8 MINS

This movie features only two major absences of music. In the first one we get a lot of setup.

“That rug really tied the room together” is a paraphrased quote first uttered by Coens associate Peter Exline, in a fit of… being pleased with his rug situation. While no character in the film is based on Exline, the story of The Dude’s car going missing might be.

The Dude assumes a Jesus Christ pose here and during the Donny debacle.

Christian references will abound, but with very little rhyme or reason to them. There’s The Dude’s first appearance, brown sandals and robe, The Stranger calling LA the “City of Angels”, or references to the crusade-like Gulf War. These are of course jumbled in with the Judaism, Eastern spiritualities, paganism, Aztec polytheism and techno-secularism seen later. I cannot find a throughline for religion in this film, save for the jeopardy of the character’s souls, a dramatic facet one could glean from most movies.

The Lebowski Manor. Festooned with plaques of real life organisations paying tribute to Jeffrey Lebowski, of photos of Jeffrey Lebowski with conservative celebrities.

The Coens love statues, statuettes and outsized ornaments as character development. The statues here are pronged, pointing, charging or stood to attention. Emphatically masculine for someone about to be a real hard-on.

The Coens also love the display of trophies as character development. This extends to trophy wives. “Trophy wife” is a term seemingly coined by Julie Connelly and popularised by William Safire in 1989 (The Dude is correct to call it a neologism). When you look “trophy wife” up, you see a picture of Anna-Nicole Smith, Playmate of the Year 1993, who played two men’s trophy girlfriend in The Hudsucker Proxy (1994), before marrying petroleum tycoon J. Howard Marshall (1905-1995), in real life, in 1994.

News coverage of this event was omnipresent and likely informative to the creation of Bunny Lebowski, as well as the creation of Sherri Ann Cabot, Jennifer Coolidge’s character in Christopher Guest’s Best In Show (2001).

Sometimes I like to just sit for a minute and imagine the Lebowski wedding.

David Huddleston starred in the stoner movie (also New Hollywood comedy, vaudeville revue, satire, musical, Jodorowski-for-Dummies, leave me alone, genre people, it conforms exactly to the genre criteria for stoner films I have laid out above) Blazing Saddles. Olson Johnson, The Mayor of Rock Ridge. Olson is a name that the Coens have enjoyed reusing in their work, along with Gunderson, Hudsucker and Tuchman-Marsh.

I think Blazing Saddles is another pivotal text for the Coens, so a quick review of similarities: Begins and ends with a cowboy not in on the joke, there are references to *ASIAN PEJORATIVE* as being the guys who built the railroads, the primary characters are a duo of a combat veteran and a laidback stoner. Excessive use of the word “Johnson”, tributes to vintage Warner Brothers cartoons, and the story about ashes flying back into someone’s face was a Howard Morris story frequently retold by Mel Brooks.

Jeffrey Lebowski gives a linguistic crash course on his characters dickishness. The insistent “yes, yes”, a tic we know he has forced into Brandt’s vocabulary. His suppression, for the first and last time, of the word “bum”, a word he will go on to use nine times. His appeal in cod-Spanish: “Parla usted Ingles?”, bellowed just as we have seen an implicitly Hispanic woman dusting his abode for him.

The Coens are partially responsible for Spike Lee’s coining of the “Magical Negro” trope, having made two films where magical black men assist the stories of white men. This movie doesn’t have a magical black person, but it does have magical Hispanic women who appear and disappear to convenience the plot. While we’re on race:

“I didn't blame anyone for the loss of my legs, some chinaman took them from me in Korea but I went out and achieved anyway.” - Jeffrey Lebowski

A sentence a therapist could spend weeks on. Look at the “conflasian” of it, conflasian being the act of conflating different attributes of Asian people, such as assuming that a person in a turban is a muslim, that karate and kung-fu are basically the same thing or that Britain’s supermarket Asian food packaging is somehow morally acceptable. Here’s the kicker though: The Dude refers to Woo with the same pejorative as Jeffrey Lebowski does, when “Woo” is both a Chinese and Korean name. He is played by Philip Moon whose surname could also be either Chinese or Korean, though he prefers the term “Asian American” in his bio.

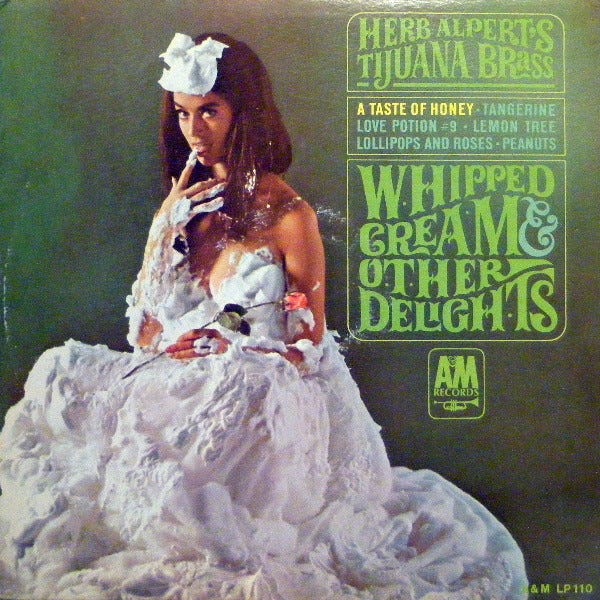

Esquivel - “Mucha Muchacha” (1962)

“Mucha Muchacha” is a simple song, a little bit of mambo. It houses a wolf whistle and a flirtatious (and dated!) exchange between a man and a woman. The Dude will later be imitating a certain fictional wolf, so lets say for the sake of analogy that his “spirit animal”, or whatever, is the wolf. Here he is having a flirtatious exchange with another mammal, Bunny, who doubles up as a Playboy Bunny.

There is a question as to whose leitmotif this is. Perhaps Bunny’s? No, there is a man in her pool, Uli. We later find out that the two of them star in a Jackie Treehorn production. This is a Jackie Treehorn theme.

Juan Garcia Esquivel is a proponent of a strand of modernism in music, sometimes summed up as “space age bachelor pad music”. This movement in music incorporates hypermodern production techniques and, later, synthesisers to produce a sort of furniture music for the modern gentleman. It represents a sort of synergy between ad men and musicians, selling titillation, sophistication and comfort on a piece of plastic, and hopefully selling a new record player, made by the same company, RCA.

“Mucha Muchacha” is fairly typical of the genre, showcasing new levels of clarity in recording, using extreme stereo panning to highlight its own three-dimensionality, while playing an established form of dance music. It’s a little silly in retrospect, now that just about all music is in stereo.

Jackie Treehorn’s once state of the art digs are starting to look a little out of step. It kind of reminds me of the Venture Compound fromVenture Bros. Nine Inch Nails collaborator Jim “Foetus” Thirlwell did the theme music for that show, sampling Esquivel.

The Monks - “I Hate You” (1966)

“You guys are dead in the water” - Donny

The Dude is a throwback who experiences flashbacks. Walter is the same. The Dude has acid flashbacks. Walter has ‘nam flashbacks. This scene is one of these.

The Monks are a tonsured rock band comprised of GIs. They were stationed in West Germany, in relative peacetime, but war was not lost on them, and they used military precision and military anxieties to form their own militant sound.

Walter tells Smokey to “mark it zero”. Smokey says “bull-shit, mark it eight”, his pronunciation of “bullshit” evoking many Vietnam War movies. Jimmie Dale Gilmore plays Smokey. He is a Texas singer-songwriter influenced by Roy Orbison and Hank Williams. I love his soft delivery. It makes you feel like he’s truly about to be shot.

Captain Beefheart - “Her Eyes Are A Blue Million Miles” (1972)

Captain Beefheart was a practitioner of a kind of psychedelic rock, his own kind. In the sixties Beefheart, a painter, made an intense rock cubism, flat by virtue of reverblessness, but three dimensional by way of distorted time. He took the oldest recorded music as inspiration for the most cutting edge music of its day. He sang highs and lows like few human beings could. His words were so intense that he sometimes had to invent new ones, like “vugum”. Captain Beefheart and his Magic Band’s music is information-dense, hard listening and if it’s your first listen, you can’t tell if he’s joking.

“Her Eyes Are A Blue Million Miles” comes from Clear Spot, an album recorded after Beefheart unclenched his anti-commercial stance and sought some form of relaxation in his music (though not in his domineering relationship with The Magic Band). The song concerns a beautiful girl, with blue eyes, like Bunny:

“I look at her and she looks at me / In her eyes I see the sea / I don't see what she sees in a man like me”

This quote from T Bone Burnett is interesting:

“What does Dude put on just after he’s made love?’ He’d come in, smoke a J, do a little tai chi, have a White Russian, listen to Captain Beefheart. That’s a man after my own heart”

Is he saying The Dude found a cash machine?

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Franz Xaver Süssmayr, Robert Levin - “Requiem (Lacrimosa)” (1791)

“Ecce homo, qui est faba / vale homo, qui est faba” These are the lyrics of the opening titles to Mr Bean. They translate to “Behold, the man who is a bean / Fare thee well, bean-man”.

In relation to The Dude, this Mozart piece, likely inspiration for the Bean piece above, carries a similar profundity, translating as “Mournful that day / When from the dust shall rise / Guilty man to be judged / Therefore spare him O God / Merciful Jesus / Lord Grant them rest! Amen!”.

In relation to Mr. Lebowski, it completes his own aesthetic habitat, his idyll. Jeffrey Lebowski is not introduced by music, but when it comes it emphasises the absurdity of his situation. An aristocrat with a butler in 1991, living an easily-punctured dream of liegedom. In relation to The Dude it is suggestive of his transcendant idiot Sun Wukong/Bean qualities.

Richard Wagner is the father of the lietmotif, a technique used throughout The Big Lebowski. He is also a few other things, a hater of Jews, an inspiration to Hitler and, uh, a talent for the ages. As composer Steve Reich put it: “I'd have been happy to blow his brains out! But: A great composer, and you just have to lump it”. Wagner comes up a few times through this film. The piece used in this scene was originally supposed to be something of Wagner’s, from Lohengrin, but it was changed, likely for subtlety.

Brandt is in a short scene with The Dude after this. It employs a technique that I’ve always called an “Edgar”, after director Edgar Wright, whose favourite move it seems to be. Basically, take two funny actors playing funny characters, have them face each other and reduce the distance between their bodies to something just south of plausible.

It creates a sort of comic tension, one often resulting in bloopers. I don’t know how many bloopers there were in the shooting of this scene, but look closely at Philip Seymour-Hoffman as The Dude blows smoke in his face and says “He thinks the carpet pissers did this?”. He’s cracking.

Gipsy Kings - “Hotel California” (1991)

The first coming of Jesus. “Hotel California” is the signature song of The Eagles, musical nemesis of The Dude.

The Gipsy Kings are a French outfit who play this song in a rumba-flamenca style (see also: “Bamboléo”). Flamenco is a musical genre which has endured through the entire 20th Century. It appears in films long before sound itself did. By the fourties and fifties, flamenco was played for musical spectacle, with stars like Ricardo Montalban and Ava Gardner in festive and sultry dances. It is still used this way, but over the years, flamenco music, used somewhat interchangeably with mariachi music, has come to be used in scores to introduce a challenger, an adversary or a stand-off. Put it this way, if Antonio Banderes appears in your movie, armed, it’s payday for at least one Spanish guitar player.

The Gipsy Kings have been able to capitalise on the phenomenon more than most, scoring Zorro on Broadway, doing “My Way” for Better Call Saul and even recording “You’ve Got A Friend In Me (para el Buzz Español)” for Toy Story 3.

“Hotel California” is already a Latin-tinged song. It eludes meaning, primarily by design, but also by the members of The Eagles ascribing dozens of different meanings to it across years of interviews. It seems to cover the occasion of the band’s arrival in California, the sights, sounds, smells, then the materialism, the vacuity and the dread. In my book it’s every bit as vacuous as anything it purports to critique.

The Gipsy Kings version was recorded for a various artists compilation, not something you’re trying to do when you’re positioning a hit. It tightens the flab of the original lyrics, picks up the energy to great satisfaction. It’s one of the only pieces on the score to feature a synth. This choral pad subtly connects Jesus Quintana to “the machine” while establishing his divinity, such as it is. Dude’s not impressed by anything but the strike, Donny is in awe, receiving the kiss blown at him as though it were seraphic and Walter’s reaction is the most curious of all. Walter’s mood throughout this scene has more plot turns than most movies. A highlight of this comes when he states that he refuses to conclude a kidnapping if it’s “during league play”, cutting himself short to tell Donny that “Life does not stop and start at your convenience, you miserable piece of shit.”, without any acknowledgement of the contradiction.

The Coens have said that they consider Jesus Quintana to be the most mysterious character in the film. This may be a preface for anticipated offense relating to his portrayal. Here’s a mystery: in the cutaway of him going door to door, Jesus has severely stuffed his underwear, something he hasn’t done at the alley. What’s up with that?

I read around the issue, and it seems his outfit in the Hollywood Lanes didn’t involve crotch-stuffing for fear of the picture getting an NC-17, which it was already dancing around. A beautiful consequence of this is that it can now be interpreted that Walter is imagining Jesus as being more well-endowed.

Bob Dylan - “The Man In Me” (1970) (SECOND PLAY)

In David Lynch’s Twin Peaks, there is a “mystery man”, who might just go by the name of “Bob”. This film has a mystery man called “Bob” too.

The audience gets a message that “Bob” is coming, if The Dude puts on side two of the tape. But wait, that’s a Sony Auto-Reverse Walkman. It changes sides automatically! Having had no time at all to take this in, the audience sees a beautiful woman with a bob, flanked by two guys dressed in double denim, kinda like Twin Peaks’ Bob. One of them knocks The Dude into the middle of side two of the tape, Bob Dylan.

In the moment before the assault The Dude appears to be gathering some sort of chi. Increasing his bowling potential, perhaps, or meditating. Either that or he’s about to jack it.

We’ve heard this number already, representing the sweet flow states of bowling. Here it does the same thing for dreaming:

“But, oh, what a wonderful feeling / Just to know that you are near / It sets my a heart a-reeling / From my toes up to my ears”

“Take a woman like your kind / To find the man in me”

Maude is a knockout who bowls The Dude over. She can be seen at the foot of the lane as The Dude rolls away from her.

Erich Wolfgang Korngold - Ilona Steingruber, Anton Dermota and the Austrian State Radio Orchestra - “Glück Das Mir Verblieb (From The Opera Die Tote Stadt)” (1920)

If Wagner gave us lietmotif, Austria’s Korngold is perhaps the composer most responsible for how Hollywood scores originally sounded.

This piece predates his days of scoring Anthony Adverse (1936), The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) and Kings Row (1942). Korngold had been a success in writing for the stage from the age of eleven. The opera that this comes from, Die Tote Stadt (“The Dead City”, originally referring to Bruges) concerns a man who meets a woman who looks just like his late wife. His attempts to court her run into conflict and he later at once fantasises about courting her and murdering her. In this piece she is playing her lute for him and singing the words “Return to me, my faithful love”. The piece is melodramatic, pining for lost love. Perhaps it speaks to Brandt’s own messy feelings for Bunny. Or Maude for that matter, isn’t that a bronze of a valkyrie with a trident guarding a rug standing next to them?

MYSTERY MUSIC #1

An advert, small in frame as Walter and The Dude leave for the hand-off. It is situated between two very cosy looking pieces of text design, a calling card for the Coens’ aesthetic, indicating that its placement is purposeful. Half a face on white with blue text, like a promotional ad for an album or show. If anyone can identify this for me, please comment below!

Creedence Clearwater Revival - “Run Through The Jungle” (1970)

Before we hear this song, there is the tiniest chance to see Walter’s place of work, Sobchak Security:

Lots going on with this exterior.

The logo is an “SS” padlock, which is a curious choice. John Goodman plays a seller of “Peace of Mind”, security here, insurance in Barton Fink, bibles in O Brother Where Art Thou?.

Considering that Walter has his dirty undies with him it might be inferred that this is also where he lives, bars across his windows. Walter normally dresses tactically, but here he is in full fatigues and bandana, something out of Apocalypse Now, perhaps the most famous use of Wagner on film.

“Run Through The Jungle” plays as we are in The Dude’s car, but it does not seem to come from the stereo, rather it sounds like it’s coming from Vietnam. The scene starts dark, but darkens further the second the song starts, invoking the grizzly traffic stop scene from Fargo. As Walter jumps from the car, the last thing he says is “Let’s take that hill!”.

Though the song is informed by the Vietnam War, the line about “two hundred million guns” actually relates to contemporary news stories that the number of guns in the United States now exceeded the country’s population. The threat within.

Booker T. & The MGs - “Behave Yourself” (1962)

This track comes from the album Green Onions, which The Wire Magazine would go on to call one of the hundred most important albums ever made. First used in a movie by George Lucas, the title track, an American Classic, is in the top ten most frequently deployed pieces of pop music on film, having since been used by the likes of Ken Burns, Franc Roddam, Barry Sonnenfeld, Rob Cohen, Matthew Vaughan and David Lynch.

“Behave Yourself” isn’t the title track, and this is possibly the only film it’s ever been in. Like “Green Onions”, it’s a twelve-bar blues Hammond organ instrumental.

T Bone Burnett is a big fan of a musician who shares his surname, Chester Burnett, better known as Howlin’ Wolf. The song “Behave Yourself” reminds me of the most, melodically at least, is Led Zeppelin’s “The Lemon Song” (1969), itself based on Howlin’ Wolf’s “Killing Floor” (1964) , both opening on the lyric: “I should have quit you / a long time ago”. Might reflect how The Dude is feeling about his friendship with Walter right about now. That, or, “Behave Yourself”. Anyways, the main background to this scene is that ringing phone.

““Aitz chaim he”, as the ex used to say” is a pretty cryptic line referring to the Tree of Life. Puts Cynthia as a little religious, no surprise there. The Dude is earlier seen wearing a baseball shirt (his own, seen also in Cold Feet and The Fisher King) referring to the Bodhi Tree. Spiritual parallels?

In posting a schedule with a game on Saturday, a German named Burkhalter (Berk halter? Naw, it’s a reference to Leon Askin’s Nazi General in Hogan’s Heroes) has put a stop to Walter’s train of thought. Walter proceeds to outline his religious position, that he is a shomer-Shabbos Jew, and an especially observant one (in one respect). This serves a couple of purposes, making Walter even more comically unhelpful, but also provoking a question about what the hell is going on in his mind. Walter is a very frequent transgressor of the Ten Commandments, but the Thirty-Nine Melachot are a no-go?

MYSTERY MUSIC #2

As the two cops talk to The Dude, this record is briefly seen on his record player. It is not a soundtrack cut, so it must be something else. I have not yet identified it, so if you have any ideas, comment below!

Police response times are notoriously slow in Los Angeles 1991, hence the oddly comfortable exit from the bowling alley after Walter pulls his piece. As such, The Dude doesn’t know when the LAPD will be coming to his house, resulting in his being baked beyond belief by the time they’ve arrived.

Meredith Monk - “Walking Song” (1997)

The Dude is very attracted to Maude. She is his wet dream. This is intimated when he enters into her space, and is left standing just behind a small puddle of fluid, as though it had come out of him.

Meredith Monk is a celebrated post-Fluxus composer. Her “Dolmen Music” provides the cello and “Ahh-Ooh” on DJ Shadow’s “Midnight In A Perfect World”, for one.

This piece is multi-disciplinary. It connects Maude to post-Fluxus art. It offers mystery, sex, Lamaze. It is neoprimitivistic.

The Coen Brothers likely connect Monk to Turtle Dreams, a work that they’d find highly amusing in an ironic way. To quote Monk on Turtle Dreams: “There's a certain fascist element to it, and I wasn't conscious of that at the time.... There's a flatness, a surface style to the people, and maybe a kind of narcissism too.”

Maude makes an entrance, her “spirit animal” the hawk, the bird of prey, maybe the dragon. She marks The Dude with green paint and offers him a used rag to clean it off while she walks to her pornography collection.

Piero Piccioni - “Traffic Boom” (1974)

Piero Picconi was director of the first Italian Jazz band on the radio after the fall of Mussoulini. His music has been in a film for most of the fifty years preceding The Big Lebowski.

This piece is in the kind of filmic funk genre associated with library music. It plays over Logjammin’, a cookie-cutter porno with a threadbare narrative pretext. For decades, porn films would often use funky library music, out of frugality, laziness and aesthetic tradition.

“Traffic Boom” is from a Lina Wertmüller film. Previously Fellini’s assistant, Wertmüller built upon Italian neo-realism to make Swept Away, The Seduction of Mimi, Seven Beauties.

In the film that this piece comes from, All Screwed Up, a film about characters travelling to the big smoke, Milan, the music denotes its busy urban setting. Horns as car horns.

In his stint as Karl Hungus, Uli is driving a German BMW. Freude am Fahren.

Dean Martin - “Standing On The Corner” (1956)

This song comes from a musical, The Most Happy Fella, by Frank Loesser, whose other musicals include Guys and Dolls and How To Succeed In Business Without Really Trying. I first heard the song as a child, on an album of music for children, which is really inappropriate, given it’s a song about being a street letch, with the lyric “Brother, you can't go to jail for what you're thinking / Or for that wooed look in your eye”. You know, for kids!

There were three more songs of Loesser’s on that album: “Thumbelina”, “The Ugly Duckling” and “The King’s New Clothes”. They’re a bit more kid-friendly, if a nude old man flashing a crowd doesn’t bug ya.

Loesser was an early pop powerhouse, also responsible for “I Don’t Want To Walk Without You”, “Baby It’s Cold Outside” and “The Boys In The Backroom”, the latter an inspiration for “I’m So Tired” in Blazing Saddles.

Singer Dean Martin, “King of Cool” represents a certain American idyll, singing from his sphere of abundance, drink in hand, about life and love’s bittersweet foibles. “Memories Are Made Of This” was featured in “The Hudsucker Proxy”, sung in his style by Peter Gallagher. The Rat Pack are today perceived as a handful of crooners, but before that, they were actors and actresses in the orbit of Humphrey Bogart.

Philly stand-up Dom Irrera plays the Tony the Limo Driver, reciting a bit from his act, an impersonation of somebody’s uncle. It’s not a great joke (guy complains three times, says “I can’t complain”), and it’s unclear in this scene if the punchline has landed. Irrera’s standup is generations removed from and yet perfectly faithful to the medium’s vaudeville origins. Stand-up is itself an American idyll in the nineties, the comfortable televised worlds of Garry Shandling and Jerry Seinfeld, both of which Irrera would visit. The exchange still serves the purpose of relaxing The Dude, along with the song, the roomy interior, the drink, before he is squeezed once more.

The song has a lyric or two to narrate what The Dude is doing in the moment: “I'm a cat that got the cream / haven't got a girl but I can dream” and “Saturday, and I'm so broke / Haven't got a girl and that's no joke / still I'm living like a millionaire”

Debbie Reynolds - “Tammy” (1958)

This is the title song of Tammy and the Bachelor (1957). Give it a go some time, big mood board film for the Coens, and Lynch. You’ve got Debbie Reynolds, pregnant with Carrie Fisher, as the swamp girl who discovers a crashed pilot played by Leslie Neilson, who sadly passed away this week. Great language, beautiful colours, a comedy of misunderstandings.

The song is the rare kind of innocent pop that coexisted with the crooners, torch jazz and early rock’n’roll. Like “Que Sera Sera” and “Cape Cod”, it’s sweet and insubstantial, but ripe to have meaning added to it. In this film it marks the sight of a woman’s severed toe. As with the severed ear in Blue Velvet, there is a person on the other end whose world opens up in our minds and it is horrible. The fifties sweetness also translates well to the diner scene in which the audience is reassured by the films least reliable person that the toe does not belong to Bunny, as a mascot resembling Bob’s Big Boy, Lynch’s own personal idyll, looks on.

Sounds of Nature - “Whale Songs”

In a continuing effort to have no genre unrepresented, we have a nod to America’s bestselling field recording album, Dr Roger Payne’s Songs of the Humpback Whale (1970). You may remember these exact whale sounds from Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home, Godzilla vs. Biollante or Kate Bush’s “Moving”.

It’s also a very socially influential record, a cornerstone of the Save The Whales movement, leading to the end of commercial whaling in America in 1986.

The sound we hear in The Dude’s ears sounds cleaner, later. It doesn’t have a credit, suggesting an origin in a film sound archive. It appears as a bootleg version of Payne’s original, of which there were many.

In actuality the recording comes from Payne himself, the follow-up Deep Voices - The Second Whale Record.

Elvis Costello - “My Mood Swings”

Elvis Costello and T Bone Burnett go way back. Costello contributed the suggestion of the Korngold piece above and he also wrote an original song for the soundtrack.

The first name in American-style new wave in Britain, Costello is responsible for some great stuff: This Year’s Model, Imperial Bedroom and the production on The Pogues’ Rum, Sodomy and the Lash. Former Pogue Cait O'Riordan co-wrote “My Mood Swings”. As a songwriter, Costello himself is an insider, a magpie, a musician’s musician.

Genre-wise, I’d call “My Mood Swings” Grammy-rock. It’s nice enough, but it’s low ambition and Sheryl Crow or Lenny Kravitz could sing it. Its only real relevance in the film is the title line, which twice signals an upcoming change in mood. In its first use, the change is environmental, with the bar of Hollywood Lanes about to shift to a state where miracles are possible, the domain of The Stranger.

Costello had his own dalliance with “the machine, man” from early in his recording career. He has used synthesisers and effects in his work, relegated to a background thing, in keeping with the structure of so much new wave rock. He was influenced by early Stiff Records label mates, including the Ohio “Chinese synthetic rock ‘n’ roll” band Devo. He was greatly concerned with fascism, as much European new wave was, and was particularly concerned about contemporary right-leaning organisations, whose movements he chronicled in song. He had his own fascist moment, an outburst of racial slurs in the depths of a shitty night out, haunting him and costing him big. He played many anti-fascist events before and after this.

Sons Of The Pioneers & Roy Rogers - “Tumbling Tumbleweeds”

Bob Nolan had a nice mysterious patter prepared when he was asked about his song. Depending on how you interpreted what he said, he was discussing the spirits of frontiersmen, reincarnated as tumbleweeds, or instead, a continuing supply of folk who live as free as tumbleweeds. Sounds like The Stranger, like The Dude, like the idea of The Sons Of The Pioneers.

The Dude can hear this song emanating from the ceiling. Considering how much time he spends at the alley, he must know its playlist, probably a cassette tape or two, back to front. The moment piques his interest.

The Rustavi Choir - “We Venerate Thy Cross” (1994)

I don’t know much about the music of the nation of Georgia, except that there are some proud choral traditions. See my Bad Bunny review for another example (it’s down at the bottom).

This traditional song appears on the Rustavi Choir’s 1990 compilation Georgian Church Songs. Like “Lacrimosa” it is graceful, ceremonious, solemn. However, it also exists in the genre of world music, extremely popular among the coffee table book owners of 1991. This scene introduces us to:

Maude Lebowski’s Record Collection (circa 1991)

Maude like The Dude is a music lover. She has all of it to hand and on display at all times.

Maude Lebowski's funhouse of conceptual art contains a lot of character and story-pertinent information, chiefly in her artworks. There is the comically large pair of scissors in front of a faint phallus, foreshadowing The Dude's castration dream and reinforcing Maude’s own predatory approach to courtship across their four surreal meetings. Her coital ambitions are laid bare in the artworks around her, the pregnant showroom dummies, the sperm entering an egg, the head in a uterus.

Conversely, my reading of Maude Lebowski’s record collection is that it is not intended to be revelatory of her character, but rather that The Dude flipping through her LPs is more of an understated dialogue between the film and its more pause-happy viewers. One such viewer has identified all of the records that appear in the scene and given the collection its own Discogs page.

First up is Stereotomy by The Alan Parsons Project. In A Serious Man, the Coens celebrate the intensity and power of the music of Jefferson Airplane. They do not strike me as fans of that band’s later incarnation, Starship. Rather they probably go along with the popular line of thought that Jefferson Airplane’s transformation into the unmysterious, quantized, sexless pop of “We Built This City” was one of the great betrayals of music history and risible for it. Stereotomy is risible. Critically panned. It sounds very like Starship, a DX7 nightmare. It’s bad in its own way too, to the point where I find it amusing to listen to purely as a series of miscalculations. Its presence in the film is therefore likely a gag.