74. Nine Inch Nails - The Downward Spiral (Interscope, Nothing, 1994)

TW: graphic stage violence, nudity, upsetting themes, i think all of them, but nothing a typical NIN fan can’t handle.

I like this album a lot. Got me right in the teens. This review will likely be my lengthiest and most granular. Normal reviews will resume after I reaquaint with sunshine and learn to enjoy Steely Dan.

That's the main reason it's long, favourite band and album on the list.

Two other factors contribute to the length. One, The Downward Spiral is probably the most sonically extreme record on here, and that gives a lot of jumping off points into music that doesn't really connect with the other 99 albums. Two, Nine Inch Nails are one of the more extensively documented bands online. Fan fervour and archivist tendencies among both fans and band mean there are all kinds of artifacts available to me. The band were themselves online early, I think they're probably the only act on here who were using Prodigy message boards in 1992.

Now my goal here is nothing less than a Room 237-level deep dive on The Downward Spiral. If you've never seen the documentary film Room 237, it is the greatest film ever made about the act of over-reading a text just because you are in love with the text. Best to watch it now, because after seeing it, you immediately want to over-read something, hallucinate stuff that isn't there, and it's better if that thing is at least good. I have tried to shed new light on every track on this album and I reckon I might have. If this piece doesn't make you want to shout “oh, bullshit!”, open tabs and listen to some great music at least once, then I have failed. I only stopped writing this article because my friends and family staged a nintervention.

PART ONE - PROTAGONIST

Eighties cinema got really obsessed with a certain kind of protagonist. Young white man, inoffensively dressed, has a garage band, trapped on the treadmill, is ready to escape small town, suburban or urban mediocrity, is turbocharged with kinetic, neurotic, almost Freudian energy, is maybe played by Zach Galligan, Keanu Reeves or Michael J. Fox. It's no surprise, either. Guys like that were ten a penny in real life America, almost wherever you went. Anyways, these protagonists would usually get wrapped up in some mystery, crime, romance, horror, devilry, that type of thing. Long may the absence of a NIN biopic continue (who would score it?), but if there was one, such a protagonist would be the starting point.

Trent Reznor got into music early, but from a taste point of view he was an autodidact. Raised by his grandparents in a small town, there was no parental record collection to provide clues and his early purchases likely included Billy Joel, Barry Manilow, Queen and KISS. First concert was The Eagles. Having pop as opposed to extreme music as a first love would set him apart from a lot of his peers. He supposedly fronted his high school's production of The Music Man (What? I'm not sure about that fact, Wikipedia. Anyone, if you have a tape of that perchance, I uh, would like to see that please). Trent played in seven or so go-nowhere bands through the eighties, mostly around Cleveland, Ohio. He was a good frontman out of the gate, there's footage of him as a young adult with Paul Weller's hair and Johnny Rotten's stare, an unthreatening aura more akin to Peter Gabriel, but bags of that neurotic protagonist energy. He could play guitar, keys, tuba, MIDI and write competent arrangements, but there was something absent in his musical life. Something that wasn't being nurtured, for a long time.

The really successful acts of the eighties in genres like new wave, post punk and synth pop all had a kind of individuality to them, something personal to them and apparent to all. Cleveland had hundreds of garage bands, most defaulting to dressing and sounding like The Police, The Cars or The Fixx. Trent has depression. In a Fixx. Difficulty engaging with people. He battles it by working. Medication, when it comes, is not the over-the-counter type.

By 1988, Trent was working a janitorial job in Right Track Studios and was simultaneously a session musician and a member of Exotic Birds and Slam Bamboo, turning up in leather while they were all in blazers and playing on their centreless, edgeless pop while philosophically betraying them at night, availing of free studio time to put his first solo album together. By the time he cut a demo, he had found the rub of what he was looking for. No more pleasantries, musical small talk, apologies for negativity. He'd stripped off the first layer. This demo, later released without approval, is pained and at times cumbersome, but shows promise. Closest vibe is Depeche Mode, it possesses their manufactured darkness and silly humour, but also the self-reflection, the lust and the very real inner tumult. It proved to be his ticket out of Cleveland.

The demo gets picked up by TVT records, who start throwing talent at it, including three excellent producers at peak power. There's John Fryer, whizz of multilayering, who had produced This Mortal Coil's It'll End in Tears and who went on to produce HIM's Razorblade Romance. There's Flood, sharpener of star power, who had produced Erasure's The Circus and who went on to produce Barry Adamson's Oedipus Schmoedipus. Adrian Sherwood, tone deaf dub experimentalist, who had produced Creation Rebel and the New Age Steppers' Threat To Creation and who went on to produce Ghetto Priest's Vulture Culture. Also on board is Keith LeBlanc, a drummer tight enough to play funk breaks for fifteen straight minutes on Sugarhill Gang records.

It's an education for Trent in production, but also performance and realization. The result is “Nine Inch Nails with Pretty Hate Machine”, ten songs, six and a half of which Trent consider strong enough to keep in rotation today.

PRETTY HATE MACHINE (1989)

“Down In It” was probably the most experimental track on Trent's original demo, a sort of hodgepodge of Prince, Art of Noise, Skinny Puppy and U2's The Edge, but with a rap flavour. And Mickey Rourke. Tons of ideas, but utterly unreleasable. Finished, it's a journal entry as sprechgesang, with the chorus “I was up above it / now I'm down in it” and, like this statement, “Down In It” is at once both funky and dysphoric. It's the band's first single, would get them in trouble with the FBI and its transformation from disjointed demo to pop song is the bands first studio miracle.

“Head Like A Hole” is a song involving power structures, maybe televangelism, colonialism or just rough sex. Its spine is an electronic body music, Nitzer Ebb kind of groove, simple forceful drums, dotted with demisemipricks and a fat Minimoog bassline in a narrow range whose notes would sound good in any order (and do, on other NIN tracks). There's a pop rock song on top of it, with a catchy power chorus of two notes sung over two chords. It also has a catchy pre-chorus and a catchy post-chorus and between them they make the song a riot to sing. A Kenyan Samburu warriors rite is overlaid, adding aesthetic chaos and subtracting from any chance the listener might have to fully understand the song's totality. It's the hit. Appears in a couple movies too.

“Something I Can Never Have” is the ballad. It is beautifully staged and performed, a lone voice, a piano, lurching ambience, birdsong, percussion like a steam train in slow motion. While the arrangement is abyssal, the lyrics are abysmal, some of the worst couplets ever committed to tape. When you hear them, it feels as if the school bully's gotten his hands on your diary and is doing a reading for his tittering friends, with your crush present. It's a powerful feeling, extremely fertile for emotional explorations in the moment. Trent's still fond of it, I think he uses it either as a controlled burn for embarrassment, or to get himself into a teenage mindset on stage.

Elsewhere there's “Terrible Lie”, verse is a slow fist pump; power chords versus silence like Def Leppard or Light of Day co-star Joan Jett, then this Vangelis-like chorus that hits like liquid nitrogen. It lifts the intro of Jane's Addiction's “Had A Dad”. The original is sampled later on “Ringfinger”. Great vocal; spiteful dominance and submissive squalor.

“Sin” is a BDSM hip-shaker full of those anticipatory couplets that Depeche Mode are so fond of writing. While the videos for “Head Like A Hole” and “Down In It” are strobing, spinning, barely-get-a-glimpse-of-the-frontman affairs, perfect for MTV brain, the video for “Sin” is a more full-on Warholian NC-17 of a thing, tied to that most 1989 of things, the human gyroscope. I grew up thinking I'd be doing virtual reality in one of those. Lyrics to the song appear in human blood, smeared on a queer punk's chest. This is as neat a transition as any into what's about to happen.

PART TWO - NINE STRANGE MEN

Pretty Hate Machine was not positioned as a smash by the label, they hoped for mid-range sales and it was outperforming that. Trent, still depressed and buried in work, played about one hundred shows with NIN in 1990. He might have perceived a lack of energy on Pretty Hate Machine which he was determined to compensate for, onstage and in later efforts. Nine Inch Nails quickly went from standing around, to miming on TV (once, never again), to those headbanging, rafter-climbing human nightmares tangled in ropes, cables and tape spools.

Connecting with the wider music industry in America means running into a lot of very strange men. I will shortly talk about some of those strange men and what they did for Nine Inch Nails in the period from ‘91’s Pretty Hate Machine to the ‘94 Self Destruct Tour for The Downward Spiral, but first, there's the clause. Trent had been dicking around in a studio, making hard-ass mixes of Queen songs, the stems of which were in the studio's desk. Even recorded a cover of their “Get Down Make Love”. Thing is, Nine Inch Nails had been contracted into making a follow-up to Pretty Hate Machine which would be “similar in genre”. Andre 3000 and Neil Young have fallen afoul of clauses like this. Basically, the label tell you who they think you are, who they think they're in business with and reject who you actually are. Never ends well. Trent kicked up a fuss, publicly admonishing his label and shopping around for others, recording a follow-up in a different genre (which, lets face it, is a pretty subjective thing which should not be contingent on your getting income for your work), in secret, and would be moved to Interscope at the end of that, describing the experience as being “slave-traded”. The result was Broken EP and Fixed EP.

BROKEN (1992)

Broken is a strange thing, sounding at times like it lives inside of a lo-bit sampler, but still being an expressive and raucous bout of rock and roll decadence. It's strong. Hard rock guitars are supposed to sound like jungle cats or wolves, but these ones sound more like Doom enemies. “Wish” is the guide to the form (recently covered by Tony Hawk?). It rips along at a Motörhead tempo and has a lot of fun with dynamics, turning the pink noise and rock maximalism on and off like a lightbulb. “Happiness In Slavery” is slower but just as propulsive, taking a New Order-style rhythm and stacking as much carnage on top of it as possible. Stress with the label is utilised but not explicitly referred to, opening up all kinds of possible readings. When the Broken CD ends, it plays 90 tracks of silence, then a couple of covers, from Pigface and Adam and the Ants respectively (Adam Ant would go on to be their guest lead singer for a couple of blissful nights). Instrumental “Pinion” sounds like ritual music for the accumulation of male sexual energy. The band would open their shows with it, either as is, or slowed down to a prolonged, buzzing climax as the situation dictated.

FIXED (1992)

Fixed isn't just a strange thing, it's a wilful aberration, a hex. All pretence of pop is gone as a cadre of upsetters ransack the original recordings of Broken and shape them into something techno-occultic and profoundly evil. It was the first NIN release I bought. I went in blind, and I went out deaf. It also on paper represents a sort of union between the heavily layered pop of the nineties (pop producer Butch Vig worked on it. His mix of Last sounded too much like a Garbage record and got chucked) and the threatening mirrors of Monte Cazazza and Throbbing Gristle's art terrorism (Gristle's Peter 'Sleazy' Christopherson is also a contributor).

On now to the strange men, there were dozens, but I'll keep it to just nine, in the interest of numerology:

1. Peter Murphy of Bauhaus, by then already practically a goth elder. Perhaps taught Trent the ways of the vampire. Nine Inch Nails supported Murphy on some of the Pretty Hate Machine dates. They also would play a blinding series of covers with him in 2008 (I showed footage of this to an ex-goth classmate who had previously lived with, and therefore nearly slept with, Bauhaus. She liked the music but got back to me with one thing on her mind: “He's bald now!?”)

2. Al Jourgenson of Ministry. Brief but tumultuous, that one. NIN supported Ministry, who were at the time living a full on rock and roll lifestyle, with nothing off-limits backstage. It was an eye-opener. Jourgenson expected that Trent could rock harder than he previously had on record, and recorded a cover of Black Sabbath's “Supernaut” with him. Al had started out like Trent, a synth-pop pretty boy, but had turned his image rogue at a certain point, making sickening, ugly, heavy music since '87 or so. The two quickly parted over personality conflicts, ending up in very different places both in terms of music and dress sense.

3. Bob Flanagan, activist, poet, performance artist, masochist and performer of Nailed (1989), a piece of performance art having nothing to do with Nine Inch Nails, but having everything to do with a hammer and my worst nightmare. Bob would later star in a couple of Nine Inch Nails videos, my second and third worst nightmares respectively. The videos were deleted, far too obscene for TV of any era. I didn't even know they bent that way. Sounds of him being physically tortured appear on Fixed.

4. Gibby Haynes of bands P, Revolting Cocks and The Butthole Surfers. Subject in various LSD experiments conducted by Timothy Leary, along with Al Jourgenson funnily enough. A lend of a Revolting Cocks record from Trent was responsible for Richard Patrick abandoning new wave and joining Nine Inch Nails as guitarist. Gibby leaked the deleted Bob Flanagan videos, leading me to see them.

5. Jim Rose, circus performer, carny extraordinaire. His signature trick was to hammer nails into his nose. The Jim Rose Circus Sideshow ended up supporting NIN on tour, showing audiences, in another way, just how much abuse the human body could take. In his memoir Freak like Me: Inside the Jim Rose Circus Sideshow he had a (probably apocryphal) story about his troupe and members of Marilyn Manson and Nine Inch Nails getting pissed and trying to knock down an exit sign above a hotel doorway, having decided that it needed to come down. Freaks, geeks and guitarists launched all manner of objects at it, pulled at it, rammed it again and again as others cheered them on, but the damn thing was resilient and stayed put. Trent emerged angry from his seclusion in the next room, sipping a mug of coffee and asked what the racket was. When they explained the situation to him he left, but not before throwing his coffee mug at the sign, knocking it to the ground to delighted whooping.

6. Jim Thirlwell / Clint Ruin of Foetus (and Soft Cell once in a while), who had a remarkable album called Nail, and a picture of him nailing himself to a cross. Didn't meet Trent at the time of their first collaboration, but turned in two remixes of his song "Wish", inflating a four minute song to a combined eighteen minutes. The remixes sound to me exactly like Ginger Baker's description of his first exposure to African drumming records and heroin.

His later remixes of “Mr Self Destruct” aren't any more relenting.

7. Jhonn Balance of Coil. Occultist, dream diarist, fellow Soft Cell fan and occasional horse rotorvator. He and Trent connected very well, and he was instrumental in making NIN a stranger, deeper band. How To Destroy Angels, a band formed by Trent Reznor in 2009, was named after a Coil EP.

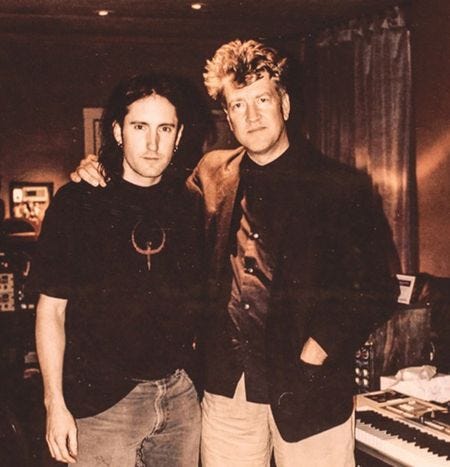

8. Brian Warner, a journalist/abuser from Florida. The two bonded over a mutual love of David Lynch, Gary Numan and KISS. Brian had a metal band who put piñatas emblazoned with the faces of contemporary authority figures above the audience. When they inevitably got smashed, a selection of meats would fall out. Brian and Trent worked together for a couple of years immediately after the release of The Downward Spiral, until parted by every difference possible.

9. Prince. Not gonna say what makes him eccentric, cause (i) you know and (ii) there are two Prince albums on this list, there'll be time down the line. Broken EP did very well, even bagging a Grammy for Best Metal Performance. NIN had sampl*d Prince in the past. Prince had been playing Broken a lot in his car (really picture that shit). Trent had been running his mouth about the industry at a time when Prince too was starting to feel like a slave. All of this culminated in a meeting between the two production giants and their entourages with a collaboration on the cards. It didn't go well. Prince walked past Trent while looking for Trent. The entourages both probably creeped each other out. I don't think they played basketball and ate pancakes together. Trent ultimately ended up publicly saying he was better than Prince (cocaine's a hell of a drug), but at least qualified such arrogance by trying to live up to it.

10. Tori Amos, of Y Kant Tori Read. No man. They bonded over a mutual love of music and... inanimate objects, dated, they contributed to each others work both as musicians and in the form of real-life inspiration from a failed relationship. Speculation about this relationship has run unchecked on IRC, AOL, fan forums, RSS, wikis and Reddit for three decades, consisting mostly of wishful projection. My own take is that even if your first album wasn't entirely about wanting someone's full attention when you're in a relationship with them, it'd be hard to form a relationship with a person with depression, medicated only by drink and drugs, in the Tate house, with an entire band of awkward, increasingly acrimonious men, working through the night to method act a nightmarish album into existence, in between rounds of ID Software's Wolfenstein 3D, while a television covered in black tape plays horror movies. I mean whether or not Courtney Love was around, that'd do it. Anyway, water under the bridge.

None of the above eccentrics were ever band members. I've only given myself a month to write this thing, but if you want some insight into the band member's minds, there's always this meticulously seat-planned discussion for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, in which no-one is bitter about any events.

PART THREE - PERIPHARIES AND PRECIPACES

When I was still in school, I didn't feel I could justify buying The Downward Spiral because it was horrendously marked up, something like £40 in 2025 money. I blame Interscope for charging out the ass on Trent's Nothing releases. Another Nothing release, Squarepusher's album-length version of Big Loada was similarly unattainable. In fact in my home town there was nothing NIN or Nothing I could justify paying for. I had heard Fixed (bought on a daytrip to Dublin) and seen one music video, “The Perfect Drug”. In order to see that I had to set a VHS to record MTV (brand new in our house) all night, hoping they'd show something cool. I was not disappointed, as the next day I heard and saw Nine Inch Nails, Slayer, Aphex Twin, Hole, White Zombie and The Deftones (and Julia Valet, IYKYK) for the first time.

Like a complete poser, I bought the album in T-shirt form at a record fair, hoping someone would strike up a conversation, culminating in my getting a bootleg. Ultimately that was what happened, following a fortuitous non-uniform day in school. First, I got a lend of “Closer To God”, a single which, as it turns out, doesn't contain any tracks from The Downward Spiral, the title track being a different entity from “Closer”, also not to be confused with “Closer (Precursor)”, which isn't on either release, but which appears in the horrifying opening credits of Se7en. There was another track on it called “March of the Fuckheads” which was completely different from “March of the Pigs”. At this point, I was well versed with remixes, but these were much more distinct entities than the usual (Radio Edit), (Club Mix) or (Dub). I knew this, because with the original out of reach I took to the Internet and downloaded the fanmade MIDI versions of the originals, which had completely different arrangements and lengths. In spite of their MIDIness, I still found them immensely exciting to listen to. I couldn't work out how the MIDI file of “Eraser” could be played by a band, even with synthetic help.

The search went on. I tried to download “Reptilian”, which is different from “Reptile”, from a website, in the days before peer-to-peer, but the file size was too large at six megabytes. I made do with the one and a half megabytes of “A Violet Fluid”, a song which wasn't a song at all by most definitions, but an unused loop, but which I couldn't stop playing, still can't. This quest went on for a year, drims and drabs of the good stuff making its way to me, like a twenty second preview of their cover of Joy Division's “Dead Souls”, streamed on Real.com at 16kbps. It felt like secret knowledge, and it was. None of my friends had heard this stuff. Booting the computer, I was presented with the phrase “Where Do You Want To Go Today?”. Where indeed?

By the time a wealthier kid offered me a bootleg, I must have heard two official hours of The Downward Spiral, without hearing either a live recording, or a track that was actually on The Downward Spiral. What was this thing, existing so far beyond itself?

PART FOUR - THE DOWNWARD SPIRAL

1. “Mr Self Destruct”

An ass whooping, followed by another ass whooping, “Mr Self Destruct” is an attempt by the band to top the perceived intensity of everything they have recorded before.

It's much slower in tempo than “Wish” or “Gave Up” but it feels much faster, sixteenth notes all over the place, rhythms stacked on rhythms. I tried to compare it to various pieces of hardcore dance music, some at an even faster tempo, brilliantly produced to sound as fast as possible, and “Mr Self Destruct” somehow still feels faster, probably by having louder rhythmic accents. In addition to sounding fast, it sounds loud. It does this quite cleverly by at first bashing you about the head with midrange stuff (Trent hardly raising his voice) then shoving a Moog up you, as you realise the bassline has been turned way down until now. “Mr Self Destruct” uses some of Ministry's kind of musical language (ruthless repetitive synthetic metal) perhaps to denote ‘decadence’, a trait ascribed to them in interviews with Trent. Ministry were at this time swilling Jack Daniels on stage like it was Gatorade. God knows what they were doing backstage, and to whom. Guitars are seething in the verse, razor sharp in the chorus and in verse two they ping pong from ear to ear to dizzy. It's an assault. The reprieve that the ultra quiet bridge gives you is no reprieve at all, because even on the first listen you know you have seconds before the beating resumes.

Insofar as The Downward Spiral can be said to have a protagonist, this song would be voiced by the devil on said protagonist's shoulder. Lyrics are straightforward enough, it's exhilaration, rot, submission of the soul. Trent would later reprise the melody of the bridge of this song on follow up album The Fragile, both on “The Frail” and the title track. He was still depressed and addicted to drugs for the two years it took to make that record, and those few notes indicate perhaps that the devil was still on his shoulder. In this song, the devil often sings in a major key. That is rarely a good sign. He is also accompanied by a chorus from Hell, first a whispering, then a sassy falsetto and finally a clew of hungry worms. This song feels more intense and out of control as it goes, partially because of that vocal, but listen also to the bassline. With every chorus it carries with it a brighter and brighter noise until it starts to sound like detuned radio static. A building numbness, senselessness, culminating in a finale from King Crimson's Adrian Belew that sounds like a blacked out, drunken wrestling match with a pig. Talking of which:

2. “Piggy”

“Pig” is a word written in blood on a door at a famous crime scene. “Pig” is a word used to describe a Nine Inch Nails fan. “Le Pig” is the affectionate name given to one of Nine Inch Nails' studios, this one, the crime scene one.

Life at Le Pig opens up at least three wells of darkness for Nine Inch Nails. The first is the spooky dark energy flowing from the Manson Murders house (mercifully demolished before the existence of Ghost Hunters). If ghosts don't unsettle, how about the occupants of the house? A temperamental creative trying to stay in the darkest possible headspace. Technicians hoping not to catch hell from said creative for not having the mic ready when inspiration has struck him. Competitive bandmates accustomed to pranks and dark one-upmanship. [CENSORED FOR YOUR PROTECTION BY THE US BUREAU OF MORALITY] and [SCENE MISSING #0062048] paid for by nervous label men. It was probably an intensely uncomfortable vibe, and if it felt haunted, it was. The second is the practical problem. If you live in the Manson Murders house, every star tour guide in Hollywood knows where you live. NIN were certainly big enough at this point that they probably had to answer the door to a few serious fans (not always of NIN either) and maybe even some runaways. Three, the reality, the reality that you have opted to live in this accursed place and to generate publicity by joking around about its darkness while the victims' loved ones are looking on aghast as Marilyn Manson and the Spooky Kids come to town. It's a guilt that does not go unfelt.

The song “Piggy” is the first from the album's protagonist. Which of the three little pigs above it is referring to is up to you. In any case it is a domestic song, choked by tight room reverb, the kind that Steve Albini filled Nirvana's final studio album In Utero with. The sound is suggestive of an individual at home, stable, but not for long.

Compared to the opener, this is lounge music, stripped down, diurnal (the crickets come and go), but haunted. You can see bone. When the drums inevitably flail away from the main rhythm, it's like a fist coming down on a table with a dinner plate on it, and all of the connotations of that. There is a melody near the end that is reprised on The Fragile in “The Big Come Down”, a song also suggestive of home amid chaos. Another motif is the lyric “Nothing can stop me now” which will echo down through the album. Trent took the infamous “Pig” door with him when he moved to New Orleans. Perhaps it was of sentimental value. Perhaps the door would still need to be used.

3. “Heresy”

There's something I'd like to get off my chest. As I undertook my own journey into The Downward Spiral back in '98 or so, I was in my own life starting to get away from God. It had begun in primary school when a teacher had spoken at length about a line in a hymn we were singing about how we “hear, in our heart”. She explained how, with God, we don't always hear things with our ear. We hear them with our hearts. It is in hearing with our hearts that we come to know God. We must always be ready to hear with our hearts. After fifteen minutes of this, another teacher sat at the piano pointed out that the line that she was exalting actually read: “fear, in our heart”. Whoops.

My secondary school was a Protestant place governed by fraudulent wisdom. It was aggressively homophobic and racist by design. Cruel to any form of perceived weakness because it saw itself as a crucible for its best attendees to go to Oxbridge, while the others were burned off as residue. Seeking pastoral care was a road to expulsion. We were shown these mid-eighties videos depicting the denizens of Sodom and Gomorrah, portrayed in the garb of New York leather daddies, a reminder that AIDS was all part of God's plan. When boys started coming out, they either left school for protection or stayed to face a kind of ridicule and scrutiny involving being mocked by scores of people at a time, often during official school events. The girls didn't bother coming out. It didn't take “shock rock” to get me there, the teachers and my fellow pupils were doing enough.

“Heresy” is a song about getting away from God. It offers up a bit of Depeche Mode's “Personal Jesus” guitar lick and employs a rhythm in the vein of New Order's “True Faith”. Talk about songs of faith and devotion (I don't think either of those bands were singing about going to church).

God has entered into an interesting place in music at this time. Rock and Christianity have been going at it, building each other up, tearing each other down since the days of Lennon's “Imagine” politely asking questions about God, and even further back to the Beach Boys using the word “God” in a song, and even further back to Sister Rosetta Tharpe performing gospel flanked by showgirls. By the late eighties this exchange has gotten to be like a war on many fronts. Industrial outfits like Godflesh, Ministry and Psychic TV bastardize the cross in their promotional materials, mostly in obscurity. In 1988, Anton Corbijn's video for Joy Division's single “Atmosphere / Dead Souls” attempts to canonize the late Ian Curtis as a rock saint, quite successfully. In 1989, Madonna's “Like A Prayer” accessorises itself with Christianity like an Unknown Pleasures t-shirt. The moral majority is incensed, Protestants, Pazder and Pope all using the unholy threat of MTV to extend their control over people. It works for them, but they fail to supress much culture. By 1991, you have Sepultura's “Arise”, Soundgarden's “Jesus Christ Pose” and REM's “Losing My Religion” all attracting censorship for utilising religious imagery, but they wouldn't be kept down for long. “Losing My Religion”, directed by Tarsem Singh, depicts living late Renaissance scenes, some of which are memorably violent. Religious officials in Ireland were unable to deduce the meaning of the song, or agree on which bit is the chorus, and so the video was banned, pushing it to be a much bigger hit than it would have been, number 5 in Ireland, relative to 19 in the UK. Human tableau videos like “Losing My Religion” become rather popular, you have The Cranberries’ “Zombie”, Nirvana's “Heart Shaped Box” (Corbijn again), Metallica's “Until It Sleeps” and of course, “Closer” by Nine Inch Nails.

“Heresy” is a violent religious riddle. There is no easy answer as to whom is being referred to throughout. More likely it is an inconsistent balance of God, the religious man and the religious right, with reference to their barbaric past and their nature in the wake of the AIDS epidemic. The chorus seems to come from the lips of the protagonist, it is important that he renounce God before accelerating his descent, like a careless act of blasphemy at the beginning of a horror film, but does the verse? I can't say.

The song has marching in its bridge, as on The Fragile's “Pilgrimage” and Year Zero's “Hyperpower!”. There are further layers of sound, a growing jangle like a parade of Hare Krishnas, and some chanting from somewhere in the developing world, uniting like an upside down Coexist. There is also a buried vocal message: “Will you die for this?” and a backwards masked vocal, obsessions of the satanic panic. This does shift the meaning of the song somewhat. One can reflect on gurus, shamans and evangelists who act like rock stars and rock stars who act like gurus, shamans and evangelists. How much of this song works if the performer himself is the God referred to, presiding over “his perfect kingdom” and “drowning in his own hypocrisy”?

4. “March of the Pigs”

Some songs are “one for the fans”. This song is “one against the fans”. They love it. Let's start with the video. ‘Mark I’ was directed by Peter ‘Sleazy’ Christopherson. There was fire, there were nude women, there were buck-toothed little people. It was aborted because everyone in Nine Inch Nails has seen This Is Spin̈al Tap. ‘Mark II’, white background, live performance of the song. Live performance still means sadomasochism to this band. They played the song all day, for a day and used the best take. It sure doesn't look like they chose take one, given that the microphone is thrown away twice and has to be picked up by beleaguered roadies and production assistants.

“March of the Pigs” begins as drums 'n' noise. The time signature is four-four, but Trent throws away a few beats along the way because fuck you. This is an interesting technique to enhance excitement. Smashing Pumpkins would later use it extensively on Machina/The Machines of God. Venetian Snares is a composer who used to mostly make evil jungle in 7/8 and that stuff is an ADHD whirlwind. Forcing you into the next bar when you expect resolution is kind of like forcing you into the next melody when you expect a resolution. The listener must adapt and fill in the blanks, be that pitch, silence or ‘deleted time’. Just when you've got a handle on the drums of “March of the Pigs”, in comes the bass like a panicking Atari ST with three bombs on the screen. Steps right up, so it does.

In my initial listen, the song felt very visual. Fast cuts of gritty tour footage that shows the band backstage and the fans out front, both projecting about one another as they get progressively more psyched up, intercut with bewildered local media and of course footage of the bloodthirsty gig itself. The verses are the most hardcore parts of the song, time-lapse montages of dawning floodlights and braying fans filling arenas. Blood, sweat and tears as collectibles. Thirst. Passion. Flailing hair. The chorus is calculation, label meetings, CD pressing plants, an exhausted performer sliding down the door of a hotel room. The piano section there for star and audience to remind themselves that the whole machine is powered by a single soul, who still has it in him to wink. “Pigs” takes on a further meaning as inferences of media speculation enter the lyrics, fans cast not only as animals but cops. Thing is, Trent and his fans realise that mutual repulsion and parasocial dynamics are part of the deal. He'll play it at just about every large scale gig these days, his poor drummer Ilan Rubin having to double up and play the piano part as well before racing back to the kit.

Trent originally talked about the song as existing before the use of “pig” to denote “fan”. He was thinking more in terms of personal betrayal, that tedium of an underground act (something NIN only were until they released music, so less than a year) selling records and becoming outcasts to the underground, targets of mooching and glory hunting, subjects of unreasonable judgement and unfulfillable obligations. “I want to watch it come down” as the refrain of backroom bitchers, active saboteurs and other man-eating schweine. To these detractors, “March of the Pigs” is quite the flex. Progressive while being rock, pop and dance literate. A macrodose of anything people could want from him, it offers something for everyone. Everyone who can take it anyway, it's as heavy as a headbutt from a combine harvester. A question is posed to the haters: “ok, but can you write “March of the Pigs”? Yeah, didn't think so.” (*MIC DROP*)

5. “Closer”

After first single “March of the Pigs” comes the second and final single, “Closer”. Nope, “Hurt” wasn't a single. Equally long, but harder to edit. Difficult to shoot a video for. Too personal. From the label's perspective, it might be implicated in a suicide or several dozen. The live version got a pseudo-release in 1995.

“Closer” is revolting, by design. The sonic equivalent of a lick on the cheek. The protagonist is sick, as is his environment. Nine Inch Nails have been a lot of places, but this has to be one of the most transgressive.

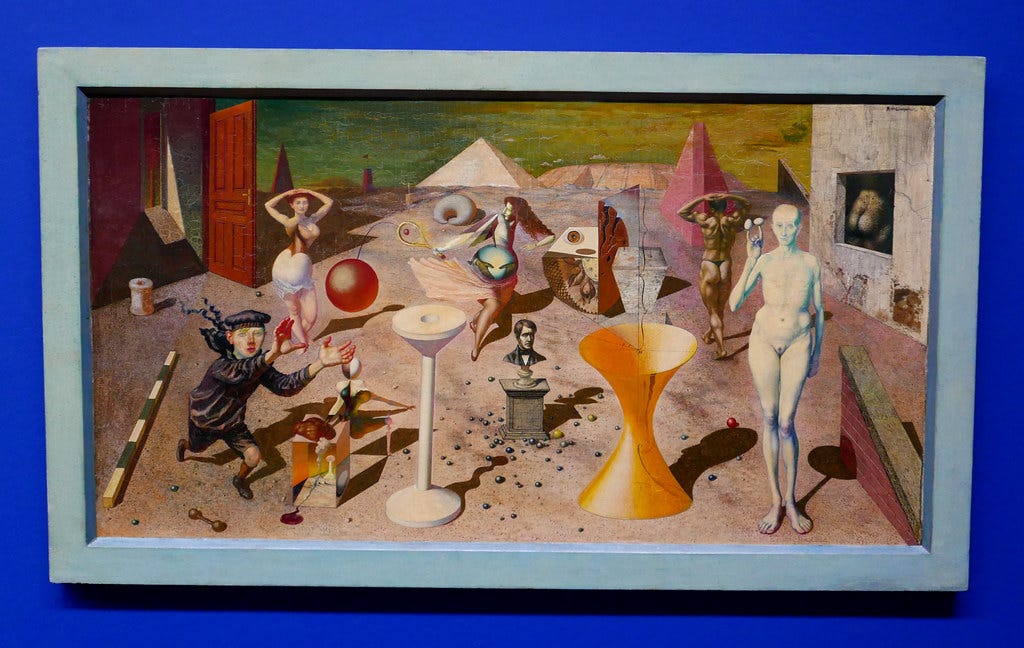

Isn't exactly easy to shoot a video for either. Fortunately, Mark Romanek. Did En Vogue's “Free Your Mind”, Lenny Kravitz's “Are You Gonna Go My Way?”, k. d. Lang's “Constant Craving”, but has a kinky side (Madonna “Rain”). It updates the “electronic musician as mad scientist” trope of say Thomas Dolby's “She Blinded Me With Science”, casting Trent as a masochistic professor of colonial Jungian dreams. Footage is hand cranked and brown, an (unharmed) crucified monkey and animated (very much harmed) pork parts against conjoined women and the nude egg spinning woman from Rudolf Hausner's painting Forum der einwärts gewendeten, all beheld by black tie voyeurs. Trent appears in multiple configurations: tortured by G-forces, iron chains and a vomit-inducing act of levitation. David Fincher was affected. So was I: there is a detail in the video that drove me into an analytical fervour, resulting in a bizarre appendix that will have to be a separate article.

The song. A beat consisting of a single kick drum and snare, at a leisurely 94 bpm (relative to the 120/240 of “March of the Pigs”), but vivid and exciting. The kick drum originates in Iggy Pop's “Nightclubbing”. Attempts to manipulate digital audio by stretching it in length without altering its pitch are not without consequences, particularly in 1993 when samplers were a little more primitive, and particularly when you are stretching things that aren't melodic notes. The result is a small but noticeable change to the timbre of the drums. The beat, well, it beats, in the manner that conflicting bass notes on a church organ might. On top of this is some analogue “fffffffff”, the sound of earphones that are turned up too loud. The beats chop through the noise, but there’s an implied warning of a high intensity expression to come. We've just heard a very loud song, so the presumption is that this intensity will come by way of volume, which is not the case. There’s a melodic synthesizer sound, a thrum somewhere in the mid range, which is not in the song's tonic note. This is a trick often used in dance music to provide a continual feel of conflict (“Don’t Stop The Rock” by The Chemical Brothers is a good example, it’s clear what key it’s in, then you get a drone outside of the key). Fading in is a string section of sorts, again, heavily treated. It’s actually a piano part, heard at the end of the song, whose notes have here been sculpted into sheer texture.

First verse. Singular closed hihat, fully quantized like the beat, panned slightly to the left, to leave space for the upcoming vocal intimacy. Filtered Bootsy Collins bassline. Drums have no swing, but this is a funk song:

“You let me violate you / You let me desecrate you / You let me penetrate you / You let me complicate you”

Protagonist is proud, lustful, boastful, proud to have achieved consent, and to be doing forbidden things but feeling disgusted too. Whispers the word “penetrate”, quietly into lovers ear, or quiet in case God hears. Open hihat, distorted to the point of heat. The “fffffffff” departs, increasing the clarity and urgency of what is to be said:

“Help me”

NIN have a prior song called “Help Me I Am In Hell”, an instrumental. “Help Me” takes on a similar connotation here, damnation. “Lord help me”, mixed with the sexier “Lord help me”.

“Closer” seems sacrilegious, but it can be religious guilt, self-loathing. The idea of consensual sex as violent and desecrating speaks to someone who either sees himself as an unworthy partner, or someone who feels the sting of a religious upbringing.

“I broke apart my insides / (Help me) I've got no soul to sell / (Help me) the only thing that works for me / Help me get away from myself”

Protagonist feels as good as damned by where he is, knows he may now be hellbound. There is a tension in to whom “Help me” is directed. Is it his partner, or God? (or the audience, whom he is also fucking by his own later definition, third reading alert!). Both have the capacity to relieve him, albeit in different ways. “Help me get away from myself”, the sinner, through absolution or “Help me get away from myself” the damned, through worldly pleasure? This is where we get the song's most famous line:

Chorus. The song's artificial bassline gives way to a more tactile and present bass guitar. The electronic beat is replaced altogether by a more physical-sounding entity, still fake, but club-sized and looser. Sleazy EBM synth. Lust:

“I wanna fuck you like an animal / I wanna feel you from the inside / I wanna fuck you like an animal / My whole existence is flawed / You get me closer to God!”

Pure id. Primal and uncensored. Disgusting and disgusted, not slightly but wholly offensive and offended by itself. “Closer” goes off live, eaten up by audiences who love being part of the lewdness. It's suitable for striptease and burlesque. It's an option for the bold at karaoke. Their queerest moment on record too, save maybe “The Only Time” and "The Collector".

The admission of nothingness, followed by the admission that his partner gets him “closer to God” carries an ambiguous meaning. Is sex a kind of temporary heaven? Is the lyric an ironic compliment to a religious partner? To be brought “closer to God” is to be brought closer to death and judgement, like a cigarette taking ten minutes off the end of your life. Alternatively, it's casual, “You pass the time” like a cigarette occupying ten minutes of your life.

The mix returns to artifice and quantization, featuring one of the most offensively cheap quantized melody lines imaginable, ascending up the scale to heaven with no hope of getting there. As the vocal kicks in, a ruined (again through aggressive timestretching) angelic chorus backs it up. Verse chorus structure repeats, hinting at the habitual nature of the singer's dilemma:

“You can have my isolation / You can have the hate that it brings / You can have my absence of faith / You can have my everything / (Help me) You tear down my reason / (Help me) It's your sex I can smell / (Help me) You make me perfect / Help me become somebody else”

Protagonist is ready to enter into an unfulfilling and dangerous relationship, one where he is isolated, self-loathing and without either reason or faith. Why? In his blinkered view he sees only a binary choice between a good life and a bad one, penitent faith and visceral lust.

Every line directed at partner or God (smelling God’s sex might be a stretch). Chorus returns, bolstered by another crude ascending line, calliope-like (an instrument that gets a nod or two in Manson’s debut, including a joke about “calliopenis envy”), more malevolent than the one in the verse. At this point the song descends into a froth of orgiastic dance. There are no more words, save those spoken into a lover's answerphone or a confession booth:

“Through every forest / Above the trees / Within my stomach / Scraped off my knees / I drink the honey / Inside your hive / You are the reason / I stay alive"

Humility, sacrament, need for pain, and sweetness. A perverse love writhing in insects is keeping protagonist alive. As we hear of bees, the guitars provide just the onomatopoeia, again with crude melodic ascent. This time it sounds like a riser, an unmelodic element in dance music which swells and builds tension to introduce a bar, but this tension does not abate. A sleazy funk synth starts up as the bees grow angrier and angrier. The final crude melody line enters. It is not ascending. It is descending. This is the melodic theme of The Downward Spiral, present also on the title track. Descent, through humiliation, self abuse and depression into the abject wreck we find at the moment of “Hurt”. As the song concludes, we hear the piano line previously used to construct the song's beginning. This is a repeating cycle, addiction. There are references to broken insides and the stomach, and pangs for more, more of this.

6. “Ruiner”

“Ruiner” is a song which has confounded readings. It's a very chopped up arrangement, alternating between this Art of Noise breakbeat thing covered in horrid VHS noise, layering all this distorted dance stuff on top, blowing itself up with distortion and climaxing in a half-step cyber cathedral. It's already a very messy structure with abrupt transitions, but the vocal is even more abrupt, changing in mood, volume, effects chain and layering, without warning. I think a big part of the abruptness is the lack of fills at the end of bars. “Mr Self Destruct” at least counts itself in, and has high-pitched guitars to signal oncoming violence, but here, you're just thrown into it. Then there's that instrumental bridge, which sounds like it comes from another song altogether.

Let's start at the bridge, and we'll work our way up to the verse. It's an early nineteen seventies blues guitar wig-out of the sort that you don't really get on any other NIN record. If “Piggy” can feel like a bender in a house, the guitar solo of “Ruiner” feels like a binge in a hotel room. To me it evokes Python Lee Jackson's “In A Broken Dream” or Floyd's “Comfortably Numb” played endlessly as a carpet accumulates cigarette butts and wine bottles. Of course, in Trent's case, the seventies would also denote childhood, and this bridge could be seen more as a childhood induction into adulthood, either through music listening or through trauma.

The chorus of “Ruiner” exists in an ordered, vast, but oppressive space. It is a procession, played once then repeated with a vocal. This vocal is treated to sound as though it comes from within, panned hard left and muffled in lowpass. It starts with something easy to follow, innuendo-laden couplets: “How'd you get so big? / How'd you get so strong? / How'd you get so hard? / How'd it get so long”. The words of a person dwarfed, at least. The second chorus adds “What you gave to me / my perfect ring of scars / You know I can see / what you really are”. The words of a person hurt, at least. The last thing that it adds is the album's second mention of the album's catchphrase: “You didn't hurt me / Nothing can hurt me / You didn't hurt me / Nothing can stop me now”. Putting those lyrics together does not add up to a clearly articulated series of actions or metaphors. As a statement it is masked, either by choice, or by inarticulacy.

The verse is the real confounder. Containing the longest sentences on the album, it has the disordered feel of automatic writing. Listening to the demo and the Pretty Hate Machine / Ministry way it is sung there, it is safe to say it was among the earliest songs attempted. Lyrics are accusatory. Paranoid. Frustrated. Atheistic. While the chorus is reflective, this feels like interpersonal confrontation, maybe a person reflexively cursing their own mistakes in front of someone before deflecting to anger, an atheist asking someone why they're still a Christian in 1993 and launching into an upper-laden tirade at them, or a couple arguing, with one party dominating and not listening. Written by a person who is struggling with self-expression outside of their music, this feels deliberately in the realm of verbal expression and its pressured speech is alienating and unsettling to its recipient. Talking of unsettling alienation:

7. “The Becoming”

Breaking up is hard to do.

It is both unlucky and unsportsmanlike to write a song in 13/8, but here we are. “The Becoming” is a broken waltz (The Strangler's “Golden Brown” does this too, in a very different-feeling 13/8), in multiple senses, waltz as musical form, as spinning, dalliance, with “Annie”, the only character on the album with a human name. Annie tends to denote “redhead”, there's Annie!, Raggedy Anne, Annie Blackburn (as in “How's Annie?”), so I'm fairly confident at guessing its real-life recipient (put it this way, it ain’t Jackie Farrie).

It's grandiose, the central line “I am becoming” echoing Oppenheimer, Manhunter. Protagonist is a grown man whose identity and soul is in decline as he fortifies his abode with teenage kicks. The lyrics are subject to psychological transference, into horror (the looping scream from “Robot Jox”), science fiction (the acoustic guitar section nodding to “Space Oddity”) and cyberpunk (“made up of wires”, electronic synthesis as a path to dehumanisation). This transference is away from addressing real and pressing romantic conflict and mental and bodily fears and retreats towards a much more comfortably noisy and immature space.

While “Ruiner” condenses its many lyrics into 4/4, and masks them with distortion, “The Becoming” has looong bars with meticulous, clear, vamping lines like: “The me that you know, he used to have feelings, but the blood has stopped pumping and he is left to decay”. “Ruiner” struggles to express the totality of itself, any attempt to understand who or what “The Ruiner” is reaches a dead end of logic. “The Becoming” has an internal logic because it is a carefully prepared statement.

The song embraces fantasy as it curses it. There is another subliminal message in the quiet part, a sample from “Angel Heart”, a satanic noir, with Mickey Rourke screaming “I know who I am!” as he breaks out of a fantasy, facing up to his own bloody crimes and damnation. “The Becoming” embraces noise as it lyrically curses it. It has a noise solo which sounds like a life-sized and visceral game of Operation, the finale is one of the busiest and most militaristic sounding moments on the album and even the snare drum sounds like TV static as our protagonist turns into a Tetsuo-like figure (either one works, but probably the Salaryman, given how much resemblance there is to the soundtrack to Tetsuo: The Iron Man and given Trent's later collaborations with Shinya Tsukamoto). Lastly, the song embraces Annie as it dismisses her. It's intentionally repellent, a “No Girls Allowed” sign on a front door, a line drawn infirmly under a relationship as the fantasy continues, not just the dark fantasy, but the impossible dream of love.

8. “I Do Not Want This”

If “The Becoming” is a “keep out” sign on a front door, then “I Do Not Want This” is a “keep the fuck out” sign on a bedroom door. It describes depression, dark nights of the soul and the dreams of a dehydrated brain. As far as I know, Trent did not confine himself to his bed for days at a time, preferring to simply punish himself all day in the studio. I think the beat of the song reflects that. I have spoken earlier about how a bar or passage can feel like a day in a Nine Inch Nails song, another example is the chorus of “Every Day Is Exactly The Same”. “I Do Not Want This” feels diurnal, with four bars to a cycle, the piano and backing vocals denoting each sunrise and sunset, the white noise denoting day after day of grim noise-shaping work. The clean piano is quite disarming here, we haven't heard one for about seventeen minutes.

The song is extremely depressed, it sounds physically and mentally drained and the dark humour is left out. Instead, dictaphones full of depersonalisation, the feeling of being “made of clay”, or impaled and “nothing” coming out. “There really isn't anything now, is there?” could be an attack on the protagonist's addressee, the listener's own heart or an attack on reality itself in the face of depression.

The chorus stamps its foot down: “and don't you tell me how I feel / Don't you tell me how I feel / Don't you tell me how I feel / You don't know just how I feel”. The last line is a good subversion of expectation, forcing the listener to engage with the request. It could easily have been “Don't tell me how I fucking feel” or something, but here, fans are instead asked to regard their hero as human, lovers are asked to listen, bandmates are asked to give space, executives to put the band manager back on the phone.

The verse speaks of lives lived, as a product of dreams or bedbound racing metamorphopsic thoughts. These lives stack on top of one another in the songs finale. Trent's vocals are ring-modded as the crazed closing lines come in. Ring modulation is an extremely unnatural sounding effect. It was used for the Daleks in Dr Who, highlighting their power, fascism and monotony, not just of speech, but thought. Trent would go on to produce Marilyn Manson's Antichrist Superstar using heavy ring modulation on vocals to denote metamorphosis and loss of humanity, in songs filled with riffs that sound like the end of “I Do Not Want This”. Another life lived vicariously. The synth bass riff of the next track “Big Man With A Gun” is teased, hidden under all this racket.

9. “Big Man With A Gun”

Even after all we've heard, there is still room to shock. “Big Man With A Gun” is a song that is skipped even by some of the most devoted fans of The Downward Spiral because of its upsetting content. On the face of it, the song depicts a rape, from the rapist's point of view. This song is open to many readings, but I definitely misread it the first time I heard it, feeling that it was about the album's protagonist running into someone worse than himself, that the protagonist was either a victim or party or witness to the rape but that the perpetrator was echoing the protagonist, repeating his “Nothing can stop me now” refrain as his own, like Frank Booth saying “You're like me” to Jeffrey Beaumont. I was wrong. Now I see that maybe no-one is worse than the protagonist of this album.

I'll return to the idea of reading the song, but first a guess at where it has come from. Interscope. TVT. Island. Atlantic. Warner. In an interview about Nine Inch Nails contributions to Quake, Trent was interviewed and praised the game Doom, firstly for its “political incorrectness”. In 2025, it'd be slightly more alarming to hear someone speak that way; these days the phrase seems more of a wedge for fascists to firmly insist that all forms of expression must be protected, as the minorities are quietly escorted from the forum by armed men. In 1993 though, a lot of cultural figures saw political incorrectness as a simpler shorthand for opposition to the moral majority, be that through Ice-T or Andrew Dice Clay.

At this time Nine Inch Nails were in a constant dialogue with their labels. Sample clearance, censorship, videos being pulled or reedited and a bunch of suggestions from executives on where they should be taking their “brand” next. Gen X hates that word, “brand”. Trent and the boys have been known to toss off a quick angry tune sometimes to blow off some steam. Good for morale and has yielded stuff like some of the punkier cuts on The Slip and presumably plenty of other discards (such as the infamous, never-finished, never-heard Downward Spiral offcut “Just Do It”, a Nike-sponsored song about killing yourself). I would imagine that this quick angry tune has come from some executive or lackey of Jimmy Iovine saying that the band needs to record another “Head Like A Hole”, or to incorporate more “street” sounds or to reach out to “rural demographics” more. It is seemingly a facet of Trent's personality that the funniest thing he can imagine doing is what the label is asking for. Hence 2009's Strobe Light, the fake Nine Inch Nails album announced as an April Fools joke, featuring Chris Martin, Alicia Keys and Sheryl Crow. “Big Man With A Gun” obliges with the demands of the industrial music-industrial complex, in the most insincere way possible, creating a self-parody. It's a sick joke. Of course, you never know how serious a sick joke is until you've told it.

Trent was at this point enthralled by gangster rap, but had no idea what to do with that. He later figured out a lot of things to do with hip hop, producing remixes for NERD and Puff Daddy, guesting on Wink's hip-hop-adjacent “Black Bomb”, getting Dr Dre himself to touch up Nine Inch Nails' “Even Deeper”, cutting a hip hop mix of “I’m Afraid of Americans” with Ice Cube and even producing an album's worth of beats for Saul Williams. This song is at a rap tempo (disguised by double time) and likely started as a sarcastic rap record, with lyrics casting the singer, a version of Trent, as a redneck fascist rapist. There are multiple references to “Head Like A Hole” including the lyric “Maybe put a hole in your head, you know, just for the fuck of it”. The bassline has the same notes as “Head Like A Hole” in a different order and it's likely played on the same Moog setting (the band used to play the two songs back-to-back without pausing). Fielding one of too many predictable questions about the length of his member, in inches, Trent sings: “I'm every “inch” a man”. When “Big Man With A Gun” was played live on the tour immediately following the album's release, with audio clips of porn on top, Trent would introduce it by saying “If anybody feels like “hurt”-ing themselves, you should do it. Now!”

“Big Man With A Gun” has been left on the record, albeit with bottom billing. Every other track on the album got a remix except “The Becoming” (weird time signatures, got an update later on “Still” in 2002), “A Warm Place” (legal reasons? see below) and “I Do Not Want This” (not sure). Why is it still there? Probably because it's up to quality. It does what the rest of the album does so well, making brick wall heaviness sound fresh. The beat is MIDI rock and roll and feels like zipping around a first-person shooter. Furthermore, in the telling of the joke, it realises itself as something more serious and disturbing. Lyrically, its meaning is still up for grabs. The protagonist could be playing videogames or acquiring the gun that is referred to later in the album or contemplating penis insecurity, impotence or premature ejaculation (at 01:36 in length, it could be said to climax early). Then there's the other reading, the face reading, that the protagonist has temporarily lost all empathy and has used this to indulge themself in a cruel sex crime, their victim given no voice or properties at all, just written out of the story. Any which way you read it, the song represents something utterly unforgiveable, especially when “Me and a Gun” exists.

10. “A Warm Place”

“A Warm Place” is an instrumental interlude, that is until someone can figure out the ‘lyrics’. Even in the age of AI, no-one has been able to transcribe the faint voice at the start. I heard it the first time I heard the track and it made me think of chatter, that the piece took place in public, perhaps homelessness for the protagonist. It also felt like a punished soul, punished with trauma or remorse depending on your interpretation of the song before it. I won't say too much more because as reader of the song (you are the reader in the end, not me), you can go wherever you like in the absence of lyrics and beats: respite, refuge, church, floods of tears, an embrace, a memory, a bed, a needle, even a hole.

“A Warm Place” resembles an interpretation of David Bowie's “Crystal Japan”. Trent and David acknowledged that the two were similar, accidental encroachment. The orientalism of “Crystal Japan” is dialled down through instrument and structural changes. To me, “A Warm Place” also harkens to Joy Division's “A New Dawn Fades”. Similar melody, and you can just imagine someone cutting the “Atmosphere” video to “A Warm Place” for an AMV.

This is an oft-streamed track due to its “suitability” for sleep playlists. I heard it in one once and vowed never to listen to a sleep playlist again. To me, there is still a colossal and traumatic echo from the nine preceding songs, which although silent, is enough to jar me awake.

Back in the nineties, this song was ambient music for people who didn't know they needed some, beloved by many who didn't know of Eno or Tangerine Dream or even Selected Ambient Works Volume II. So many fans online said it was their favourite song, and went on with their lives listening to nothing else but industrial and metal. Maybe they didn't know better, or maybe they have filled this particular song with meaning for themselves, perhaps with some suggestion from the title. It could also be the composition itself, which is less minimal than one might think. Try listening to it and counting the number of instruments in play, even identifying what they could be. It's very difficult, is it four or ten? A lot of the instruments are treated, some are a guitar run through delay, others are something more convoluted. I think I hear a synth patch given adjustments and effects slowly through the song. At least one other part is a keyboard-transposed sample of the reverb tail of something once physical. My own favourite comes in at 02:07, a high string part whose rhythm sort of collapses after two clear notes into becoming a warbling pad, which then takes on a very fuzzy bit of flanging.

“A Warm Place” isn't the last moment of beauty, but given the album's structure so far, we know that its serenity will most likely herald something very ugly indeed,

11. “Eraser”

such as a multi part sax solo, as played by the baby from Eraserhead. I tend to interpret this most abstract, but surely oral sound as a growing thirst, for more of what the protagonist desires, something that grows the day or days after “A Warm Place” and begs with increasing neediness to be appeased, changing from a crude rhythm into a debased raag. Other listeners have many times interpreted this sound texture as a heaving mass of unthinking organisms, some fearful hallucination. “Eraser” serves as a blueprint for so much of Trent's later instrumental work, rigid rhythms, detuned instruments, juxtaposition of the monolithic with the miniscule, serving a slowly emerging melody to give it spiritual significance. It's remarkable how far the songwriting has progressed away from itself in the year or so since Broken.

The drums and bass are rock solid, but awkwardly patterned in 6/4, as emphatic in their rests as their forceful hits. The albums slowest build adds twin guitars, the left one expanding to fantastic swaying size as the right one gnaws away at reality. The ascent is built on small movements, reverb tail, amplitude decay, slightly more breath in a reed, but it feels like a monkey on the back growing to the size of a dragon. A melody is well hidden towards the end of the build-up, almost completely buried. It's the natural bassline to the theme of the Downward Spiral. Making it even harder to perceive is the ascent's final riser, a racing Megadeth chug.

Post rock won't be fully coined as a genre for a couple of months, but this is a fair description of what the opening of “Eraser” is offering (Mogwai, Tortoise and Godspeed You! Black Emperor will soon be in similar territory, more likely as a consequence of listening to Pink Floyd, Funkadelic and lots of German experimentalists rather than Nine Inch Nails). As unsettling as such an arrangement may be, it is still possible to become oriented within it. As you think you might be able to, it all shrinks to nutshell size. The instruments become a simple piano, bass and drum. The vocal is clean, it's all verging on normal, but something is amiss. Every word is monosyllabic. Every sentence is two words. Guitars are devoid of melody and sound like the guts of a clock, or a timer. The lyrics are base, animal urges, a waking life reduced to an overriding want to ride the crest of an oncoming wave of debauchery. Accounting for key and syncopation, this vocal fits neatly onto the melody of The Downward Spiral, try singing the words over the ending of “Closer”.

As hard as it is to be depressed in ones bed, it is even harder while inebriated on ones feet. Go to a busy town square in Europe at the time the bars are closing and you might see a young man who can hardly walk, forced to crowdsurf endlessly on the noise in his head, screaming as a substitute for a peace that won't come. To me the brutal ending of “Eraser” replicates this horror. The arrangement is solid, a Wall, the wave form is just blackness. A heavy loop would have sufficed, but this goes far further by shifting focus while at one hundred percent volume, a maddening production feat. Trent is a Pink Floyd fan and I think this is a technique from The Wall that he was interested in superseding. Digital sound is like a box and an utterly full box should not be able to contain movement. “Eraser” breaks the dictum, its centre can't rest, even in a full box. Drums bash around the splashes and toms, the bass is cranked harder than ever, guitars flail like Leatherface, the clocks retreat into the noise, the vocal not only retreats into the noise, it becomes the noise. It does what the ending of Pink Floyd's “In The Flesh?” does, but with zero headroom. When it all pulls away we hear the horror string section. Was it there all along?

12. “Reptile”

The first depiction of Hell that I saw on film was in the comedy Bill and Ted's Bogus Journey. That film's netherworld, largely drawn from album covers and Heavy Metal Magazine, portrayed damnation's gate as a plunge into a black abyss, a crash into an abrasive red foundry before being pulled on a chained stone, by Satan, towards a metallic dragon's head as he seals you in an iron vault with a personification of your deepest fear, for all time. Any levity the film was offering at this point was lost on me. For me, then an inflexible believer in the teachings of Christ, this was every bit as frightening as The Exorcist. Even now it's still my go-to when I am stuck ruminating on infinity. “Reptile” with its combination of the mechanical, natural, unnatural and supernatural takes me somewhere similar.

Another suggestion of a monster. Mr Self Destruct, The Ruiner, the Eraser, now we are teased with the properties of Reptile or “She Who Has the Blood ov Reptile”. We come to know her more and more and less and less. She is Gorgon, Succubus, Nāga, Scylla, Shahmaran, Nure-onna, Ligorio's Echidna, Siren, Jezebel, Baphomet. A living gateway to Hell. The song opens with a sample of distant machinery, lifted from a film with an appropriate title, Leviathan.

The interior of the song is extremely hot-blooded, surely our protagonists blood. There is an oriental (D mixolydian, I'm told) scale, plenty of devil's intervals. Oriental as in the 'rock orient', by the way, not any eastern country with a name. Think of other erotic rock dances with the serpent, Shocking Blue's “Love Buzz”, Roxette's “The Look”, The Kinks “You Really Got Me”, Led Zeppelin's “Kashmir”, the latter of which incidentally sounds like it might have inspired NIN's “Quake Theme (The Bad Place)”. One can imagine a shitty cover of any of these lust songs by an LA / Las Vegas metal band in the Mötley Crüe mould, and you just know they'd break out the sitar sound on the keyboard.

The exterior of “Reptile” is cybernetic, ticking. Hydraulic limbs stamping, doors opening to daemons. I investigated this origin of the particular “servo” sound effect, trying to figure out what gives it such oomph. Up top it is purportedly Ripley using the Power Loader in Aliens. Underneath, wouldn't you know it, is a pitched up sample of a snarling pig. At least I think it is, could be aliasing, you decide.

There is the slightest of syncopation in one inhuman element of the percussion, that reminder that repetitive machines rarely repeat themselves in 4/4. The effect is like early dubstep percussion, drums pared back to give heft, a clear groove and lots of room for bass.

When the bass comes, it's actually a full step below the key of the song, only when the vocal starts does it rise up into its salivating fullness. It uses a technique also found in Spin̈al Tap's “Big Bottom” in that it's a bassline so emphatic that four band members are often drafted in to play it live. Lyrics are just the right amount of mysterious and pervy that Peter Murphy, Gary Numan and David Bowie all ended up wanting to do them justice. Peter nailed it, not sure about Gary and David.

After a drop (“give it”), there is a dissonant cry from Hell, the size of a kaiju's roar, pitched up an octave or four, reverb and all. It rings out, pitched up in mocking echolalia as though it were the orch hit from “Beat Box (Diversion One)”, “Owner of a Lonely Heart”, “Show Me Your Spine”. The melody of it recalls “Terrible Lie”. “Reptile” has a lot of commonalities with “Terrible Lie”, making me wonder if there is a link beyond the formal. Both are sluggish and powerful, share synth patches, power chords which are followed by huge, cyberchasmic gaps. Both have lies as a central theme. Both have the vocalist crying uncle as he enters the last act, that ascending bridge, climbing up towards grace only to be pulled back down. The “Reptile” version of this features a sample from The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Pam walking unknowingly down towards Evil, with skinny dipping on her mind. The melody climbs up hopefully to that barest of utterances: “Oh” (live, it's “Please” as in the “Please don’t take it, don’t take it, don’t!” of “Terrible Lie”), only to be dashed back to the ordered machinations of Hades, our protagonist wailing the blues from the torture rack.

13. “The Downward Spiral”

Jeff Ward was a drummer in NIN for one year and played in many other related bands: Ministry, Revolting Cocks, Pigface. He died by suicide in March of 1993 having lived under heroin addiction. The album has a dedication to him. Jeff's life and death are not openly discussed much, even by fans of these bands. His death is instead a trauma expressed in music, by Filter on “It's Over”, a song about his death, but reverberating also through The Downward Spiral in unknown ways. The Filter song (Filter's Richard Patrick was a member of Nine Inch Nails until the label suggested he do a pizza delivery route on the side to help boost his income) is telling, because it is furious at him. Rock music with its depressed mortality has a tendency to produce reflexive anger towards the suicides of others in the same perilous game. I think of Liam Howlett's initial rage at the death of Keith Flint. Or Trent, who in 1994, when given a surprise interview question on the recent death of Kurt Cobain, spontaneously attacked him. There is more to suicide than sorrow.

“The Downward Spiral” is a suicide in music. It explores a suicide from multiple perspectives at once, both emotionally and in the sense that the protagonist seems at once dead and alive.

The samples on this song are from Alien and Dead Ringers, but they are only a textural murk. The song's rotten base is a mass of flies and what sounds like a weathered crank turning uselessly. On top, the final use of the musical theme of The Downward Spiral. There are other textures, depressed breathing, a ‘snare’ of escaping air. There is also a discordant Mellotron, John Lennon's, on loan from Jimmy Iovine. Nothing seems aligned in rhythm or key. A short second section offers a guitar riff, limp and aimless. A snatch of harp. Flies, panned to the inner ear. Suddenly every instrument is gone and replaced by a heavy metal dirge, extreme lowpass filtering like a pillow to the face:

The bleak riff recalls Sabbath, via Type-O-Negative's song “Gravitational Constant_ G = 6.67 × 10-8 cm-3 gm-1 sec-2”, the opening line to which is “One two three fo', I don't wanna live no mo’”. Members of Type-O-Negative stated that Trent regarded their first album as an influence of some kind on The Downward Spiral. If true, this seems one of the only ways to square that circle. Suicide is a central subject in the music of Type-O-Negative, see also “Everything Dies” and “I Don't Wanna Be Me”. Poor Peter, he had a hard mind to live in. Within months, Type-O-Negative would go on to support Nine Inch Nails.

The drummer on “The Downward Spiral” is Andy Kubiszewski, formerly of Exotic Birds and later Stabbing Westward. This is the only NIN track that he ever played on and accounts say that he was asked to play shittier and shittier versions of the drum part, like some kind of reverse Whiplash.

“He couldn't believe how easy it was. He put the gun into his face. Bang. So much blood for such a tiny little hole. Problems do have solutions you know. A lifetime of fucking things up fixed in one determined flash. Mmmmmm. Everything's blue in this world. The deepest shade of mushroom blue. All fuzzy, spilling out of my head.”

The tone of the voice is hard to pin down. It's villainous, contemptuous, envious, and luxuriating in the moment. Pads sigh to the tune of an unending scream. It's not enough that the music is muffled, it is also breaking up, invasive speckles of silence. The “deepest shade of mushroom blue” is such an unexpected and gorgeous metaphor, whether it comes from entoloma hochstetteri (blue pinkgill, very blue to look at) or panaeolus cyanescens (“blue meanie”, distorts colour perception when eaten). Before there is time to make sense of it, it's all gone, transmission breaking up, transmission lost, a song about the ultimate resolution, unresolved.

14. “Hurt”

Is it future, or is it past?

After twenty one seconds of nothingness, the signal is hacked and the transmission resumes, but it is still weak. Guitar and vocals are frayed, along with the narrative possibilities.

“Hurt” is the “something” of The Downward Spiral. There are a lot of terms for a song of mortality or finality. Which one to use? “Closer” is out, too awkward on the page given track 5. “Eulogy”, “requiem”, “epilogue”, “culmination” and “coda” are out too because I have heard them enough to not give them much thought anymore. I'm going to therefore say that “Hurt” is the “consequence” of The Downward Spiral.

Gone are the rhythms, the riffs, melodic motifs, scary monsters and super creeps. An album that has so consistently invited you to listen for details is now giving you nothing you can grasp onto, nothing but a hover of flies, that dissonant melody and those lyrics. Voice turned down to the volume of a detail, decentred. Listen to the sounds.

“Hurt” is a dirty song, dirt as a cloying and tangible nothingness. Dirt as impermanence, maladjustment, rejection, legacy. As memories, with burdensome weight. This weight is evident in the vocal performance. There is a certain habit that always comes up when you read about the producer Flood. When singers would repeat their vocal takes, he would always lean away from the pitch-perfect rendition, and towards the emotional take. It's an approach he must have used a lot on The Smashing Pumpkins' Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness and PJ Harvey's To Bring You My Love too. The vocal take on “Hurt”, recorded after a series of frustrating mistakes, is as raw as it gets: the choking effect of the thematic pain, the sensuality of the end, the very real loneliness.

We can glean from Trent's words in the “Hurt” episode of the recent pop documentary Song Exploder, words which I might add are more chopped up in editing than the drum solo of “The Perfect Drug”, that “Hurt” has revealed itself more to him over the years. I know that to Trent and many of his fans it may well be a song of healing now. That's wonderful.

You don't know what a song is or could be till you've written it, and even then that could just be the start. Case in point, one time I was watching TV with my wife, a friend of ours and a very bossy cat who couldn't abide the friend. We were watching the film Adaptation. Suddenly, there was a montage, featuring time-lapse footage of insects eating a dead fox. My wife exclaimed “I have seen that exact fox rotting. Fuck! Where have I seen that?!”. We paused as a lively discussion ensued about that dead fox. I think some of us felt that maybe we'd seen it in our respective biology classes, but we all felt that we had seen it someplace else. My wife remembered it being in an episode of Wonder Showzen. Our friend said it had maybe been in the titles of True Blood. I said that it was clearly the rotting fox from the back projections on Nine Inch Nails live video for “Hurt”. We were all correct. Consider the résumé of that dead fox, going from a sinister timelapse experiment to stock footage to Science 101 to rock stardom, prestige arthouse cinema, ironic gonzo comedy and finally low camp. Chaotic are the fates of anything and anyone that can capture the popular imagination.

There's not a lot of country on this Apple List, so tip of the cap to Johnny Cash. When he does his own version of a song, it is often mistakenly thought to be the original. In fact, when NIN graced my pitiful country with an appearance, the nation's premiere paper was all too delighted to report that the band had closed their set with a cover of Johnny Cash's “Hurt”.

I don't know how much thought The Man In Black was able to give his own rendition. He was quite prolific at the time and my guess is that he tried to make it passable, raw, quickly, so that he could return to singing some more familiar songs, as opposed to making it into his “My Way”. There are changes to the vocal, mostly obvious choices. He rejigs the timings (Cash: “I”) to something less sexually curious and glam (Reznor: “I”). Cash scoops his voice into the tonic like a labourer slinging it onto his back (Cash: “today”) instead of trying to be romantically dissonant against it (Reznor: “today”). Reznor feels the end, Cash just gets through it without hesitating. The NIN studio artifice is removed, but a new one is added, a subtle riser of volume and saturation at the end, a special effect probably snuck past Mr. Cash. Trent's crescendo is different. Modulating only his emotional tension, he just about makes it to the end. A prepared bomb is detonated. Three chords, the last featuring his signature interval, ringing on into the infinite. Down curtain.

Mark Romanek directed the video for the Johnny Cash version, completing his Nine Inch Nails movie monsters trilogy: Frankenstein, Dracula, Johnny Cash. He shot it in a derelict Johnny Cash Museum, The House of Cash, Tennessee, a different location imbued with tragic rock'n'roll significance. June Carter Cash had four months to live. Johnny had seven. The museum itself would burn down in five years. What does this version offer beyond proximity to tragedy? I think a dignity against the indignity of death. A flash of modernity illuminating an old soul, like the Vampire Weekend poster in my wife's favourite film The Wrestler. Some go further, an epitaph for country music. An epitaph for the man's man.